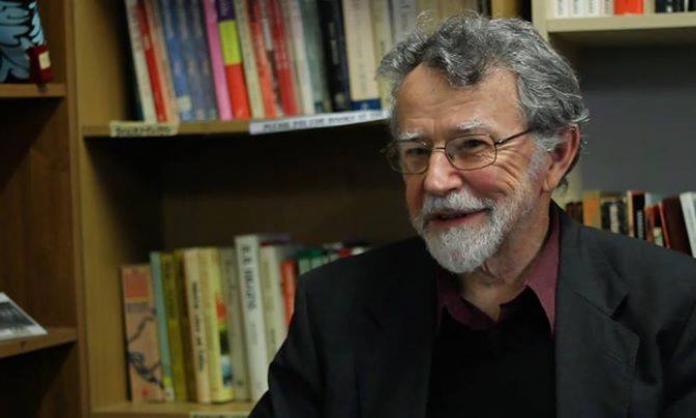

John Percy, a central figure in the development of the Australian revolutionary socialist movement over the past half century, died on Wednesday 19 August in Sydney, after suffering a severe stroke on 20 July and another on 13 August.

Throughout his political life, John was a revolutionary party builder. “Party builder” was the highest praise he could bestow on another political activist.

John and his brother Jim, his closest political collaborator until Jim’s death from cancer in 1992, were key figures in the radical anti-imperialist wing of the movement against the Vietnam War in the 1960s. Their early political development was influenced by individuals who had been part of or close to the Trotskyist movement in Australia during and after World War 2, and this helped them to understand and oppose the class-collaborationist politics of both Stalinism and social democracy.

John and Jim’s perspective was that it was necessary to start, now, toward building an eventual mass party that would be capable of leading an Australian socialist revolution, in the way that the Bolshevik Party of Lenin had been able to lead the Russian October Revolution. In this, they differed from most of the activists produced by the 1960s radicalisation, who tended to look for fundamental change to “left” capitalist politicians and/or movements that would somehow know spontaneously what to do next.

As well, Vietnam’s struggle, the influence of the Trotskyist Fourth International and events like the Prague Spring and May 1968 in France gave them an unshakable conviction that the party they sought to build would have to be thoroughly internationalist in both theory and practice. John’s many contributions to building an international movement included 18 months in 1974-75 working in New York on Intercontinental Press, the revolutionary news magazine produced by the US Socialist Workers Party on behalf of the Fourth International.

Before Vietnam’s victory over US imperialism, “the Percy brothers”, as they were widely known, had managed to assemble the political activists to create, first, a youth organisation (known as Resistance and Socialist Youth Alliance at different times) and then a party nucleus, the Socialist Workers League, later called Socialist Workers Party, Democratic Socialist Party and Democratic Socialist Perspective until its political degeneration and dissolution in 2010. (For convenience, I will refer to the organisation as DSP despite its actual name at any time.)

It is difficult to write about John without writing a history of the DSP, because he was always centrally involved in initiating and/or implementing its major activities. Here I will try only to indicate some of the qualities that made him an outstanding revolutionary activist and leader.

John had an outstanding ability to combine firmness of political principle with great tactical flexibility – primarily because he had a very clear understanding of the difference between the two. The importance of this was reinforced for most of us in the DSP in the 1970s by seeing how the conversion of a tactic into a principle contributed to the US Socialist Workers Party’s transformation into a sectarian cult.

This combination was important in allowing the DSP to discard an outdated attitude toward the ALP in the 1980s and to relate to the sudden emergence of the Nuclear Disarmament Party and then the Greens. It contributed to successful fusions in the 1970s and later also allowed us to explore the possibilities of unity with the Communist Party of Australia and the Socialist Party of Australia, without suffering any political disorientation when those processes came to a dead end. We were accustomed to changing a tactic if it wasn’t successful.

John was good at party building because he was a team builder. He helped the DSP create a conscious culture of developing the skills of each member and combining them into a whole that was often more than the sum of its parts. This included particular attention to the training of women cadres and comrades from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Different members of course had different abilities, and one individual or another might be known as having outstanding skills in a particular area, but they were encouraged to develop many skills, to become rounded revolutionary cadre rather than limited specialists. There was no “star” system; John and other leaders, in both word and their personal example, emphasised that all the tasks of party building, including the most mundane, were to be valued equally and carried out by all members, as professionally as possible.

John himself led many different areas of party work, including being a branch organiser, editor, writer, national president, national secretary, public speaker. He was widely known both inside and outside the DSP as the partisan of a regular, attractive and party-building revolutionary press. Over the years, literally thousands of people met John selling a revolutionary paper on the streets of Melbourne or Glebe, at demonstrations or picket lines, wherever he could come into contact with people who might be thinking about politics.

While national secretary of the DSP in the 1990s, John also made a tremendous contribution to developing the party’s internationalism. The DSP withdrew from the Fourth International in 1986, deciding to base its international relations no longer simply on membership of an “International”, but on similarity of basic revolutionary outlook, no matter from what tradition parties originally came. It was during John’s time as national secretary that this perspective fully bloomed. The DSP established close relations with parties in the Asian region, but also in Europe, that had no connection with Fourth International Trotskyism. Some had evolved from an earlier Maoist tradition. Some had no connections with any pre-existing currents.

This new approach made it possible for the DSP to hold a series of international conferences with probably the largest representation of revolutionaries ever organised in Australia. John’s role was key as a central party leader, but he also made specific contributions, building relations with the Communist Party of India (ML - Liberation) and with Lalit in Mauritius. John later toured India, meeting CPI (ML) leaders and addressing rallies of thousands of workers and peasants in a way that CPI (ML) leaders described as “like a lion”.

But perhaps his greatest contribution was in initiating and organising international collaboration on a new magazine, Links. This was a unique publication in the history of the international revolutionary left. It was a publication at the core of which was collaboration between revolutionary parties, inspired by the Leninist party idea, no matter what traditions they had emerged from. It was a place where ideas could be exchanged between parties. Leaders of important parties were represented on its editorial board.

John also understood the importance of revolutionaries studying and learning from their own history and experiences. John was always the unofficial DSP archivist, collecting shelf upon shelf and filing cabinet upon filing cabinet of documents, leaflets and posters from the Australian left. (A selection from his poster collection is scheduled for display at the Addison Road Community Centre in Marrickville, Sydney, in October.)

In the 1990s, as long-time party members began to feel their years and capitalism celebrated what its propagandists claimed was a permanent triumph, John pushed the idea that comrades who had important party assignments had a responsibility to “train your replacement”. Revolutionaries had to prepare for however long it might take to construct a mass Leninist party.

But in the atmosphere of “the end of socialism”, many leaders and members of the DSP began looking around for a way to avoid that long and difficult path. A tactical experiment, of attempting to create a “broad left” party, the Socialist Alliance, as a more concentrated audience for revolutionary ideas, proved instead to be a heavy burden on DSP resources.

John and a minority of DSP leaders therefore advocated pulling back from the Alliance tactic. But a majority turned the tactic into a principled strategy, insisting that events would shortly bring an influx of members into the Socialist Alliance and propel it into an important position in Australian politics, including electoral politics. In the hope of such a development, they began replacing the DSP’s revolutionary program with reforms that they thought might be electorally attractive.

The differences broke into open debate within the DSP in 2005. Despite the failure of all their hopes for Socialist Alliance advances, the majority refused to change course, and in 2008 they expelled the entire minority.

As one would have expected, John played a central role in the expelled minority’s regroupment as the Revolutionary Socialist Party. It was a difficult time, and two years later a substantial minority decided that it really was impossible to build towards a revolutionary party in the current climate, and they resigned from the RSP.

For John, health problems added additional difficulties. In 2008 he was diagnosed with throat cancer. This was eventually treated successfully, but involved months of X-ray and chemotherapy that drained his time and energy and left various side effects on his health.

However, an important change was on the way. In 2012, Socialist Alternative approached the RSP with a proposal to explore the possibility of merging the two organisations. Since the major historical difference between the two tendencies – on the class character of the Soviet and Chinese states – had been removed by the changes in Eastern Europe and China, and since SA, like the RSP, was clearly committed to the construction of a revolutionary Leninist party, this was an eminently sensible proposal. At a conference in late 2012, RSP members voted unanimously to join Socialist Alternative, and this process was completed at SA’s annual Marxism conference at Easter 2013.

John was of course one of the RSP members elected to the National Committee of Socialist Alternative. Despite signs of declining health, he threw himself into building the united organisation, especially into distributing its new newspaper, Red Flag. He also continued his decades-long solidarity with the people of Vietnam as part of the Agent Orange Justice campaign.

Two years ago, John passed out while selling Red Flag on the street in Glebe. He had suffered a small stroke, which in itself was not too serious. But the doctors’ examination revealed another condition, an untreatable aneurysm in the brain. They described this as a “time bomb” that could kill him at any moment.

John responded by redoubling his efforts to complete his three-volume History of the DSP and Resistance, the first volume of which was published in 2005. The aneurysm struck before he could do so, but it may still be possible to compile his notes and completed passages into a useful text for current and future generations of revolutionary Marxists.

Among the many lessons in that semi-completed history is one that stands out despite being only implicit in the text. John never wavered. Neither should we.

John Percy, presente!

Source: https://redflag.org.au/article/john-percy-revolutionary-party-builder