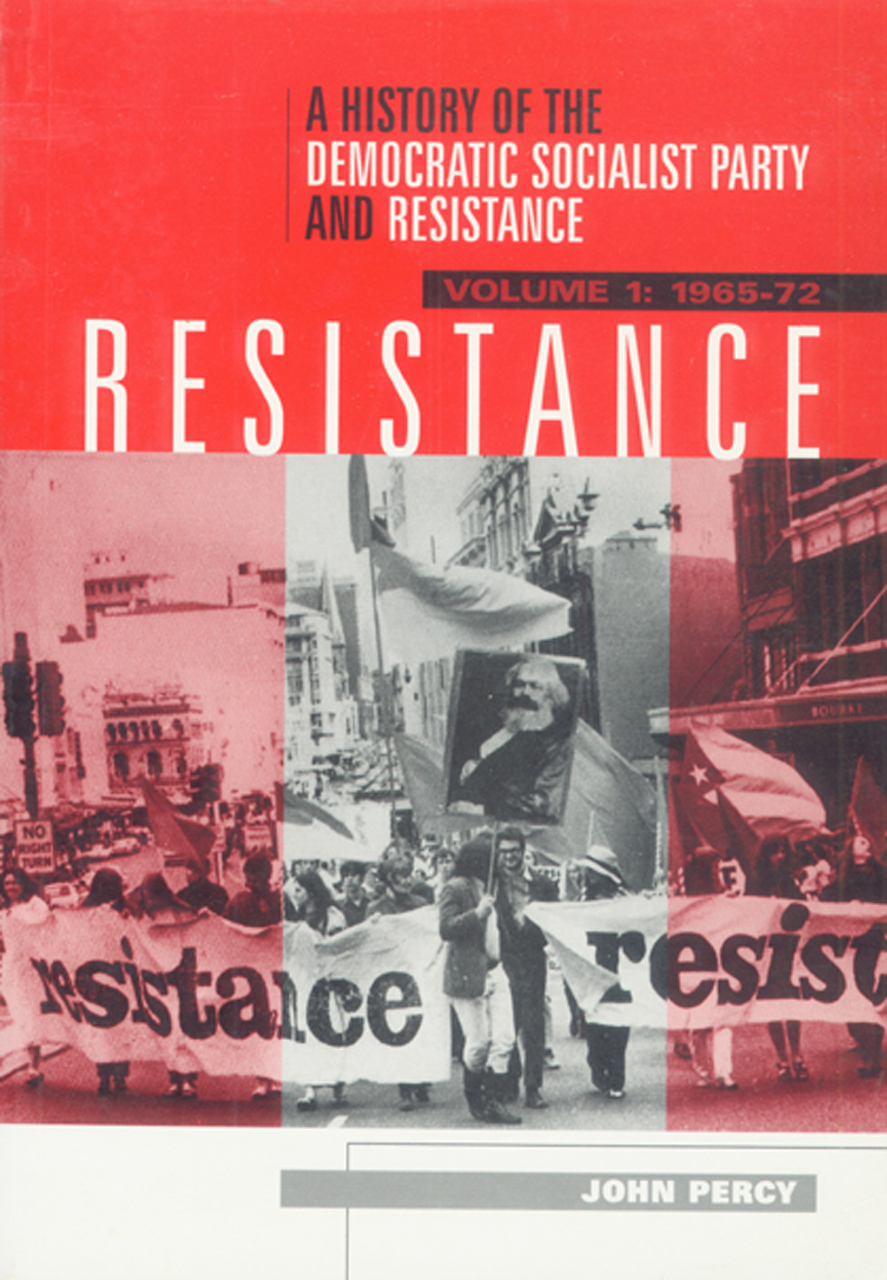

- Resistance – A History of the Democratic Socialist Party and Resistance. Volume 1: 1965-1972. Available from Resistance Books 2005

Introduction

The Democratic Socialist Party, formerly the Socialist Workers Party, has a rich history. The socialist youth organisation Resistance has a slightly longer history. This book – many years on my “must do” list – is an attempt to make that history of the DSP and Resistance accessible.

The original intention was to cover this history in one volume. It soon became clear that three volumes would be needed. This volume covers the period from 1965 to 1972, our beginnings in the youth radicalisation of the 1960s and the fight against the Vietnam War, the formation of Resistance and the founding of the party. A second volume will cover 1972–85, the political and organisational consolidation of the party and its participation in the Trotskyist Fourth International. A third will go from 1985 to the present, as the DSP sought to regroup left forces in Australia and internationally and today takes the lead in the process of building the Socialist Alliance.

The socialist movement always needs access to its history, to learn the positive lessons from its past and to avoid repeating mistakes. This is even more important when there are so many new young comrades, who have no experience, and often very little awareness, of that early history and the many rich lessons associated with it.

Although at first intended as a history for members and supporters of the DSP and Resistance, these volumes will also have a broader usefulness and appeal for those interested in left history. The youth radicalisation of the 1960s and the movement against the Vietnam War had an especially important social and political impact then and for generations to follow, but unfortunately the period has not been well served with useful accounts of the events. Many books have been written on the new left and the 1960s in the United States, but most have suffered from biases, written by conservatives or once-were-radicals expiating the sins of their youth. Not much has been published in Australia, and most of what has been written has been distorted and unbalanced.

This account of those years is very open about being partisan – it’s on the side of those who struggled for a better world then, and who, more than three decades later, still think it was the right thing to do.

There are other biases also. This account is inevitably partly personal. However, I’ve attempted to make it as generally useful as possible as a record of events, an attempt to draw out the big picture and a source of political lessons and practical experience, the dos and don’ts for the next generation.

However, because of the partly personal perspective, the account is slanted towards developments in Sydney. Of course that’s where we began, and where our national office has always been located. I’ve tried to fill the gaps by consulting comrades with experience in all other cities where we have branches, and have invited comments and recollections at various stages of the writing.

With this book I hope to be able to draw out both the political and organisational lessons of our history. Of course, these are intertwined. But we recognise that organisational questions, party-building questions, are very much political questions, and are extremely important. In fact, this was one of the early lessons we learned.

And it’s useful to be able to illustrate our political growth and development with some of the political struggles the party has been through. We realise that we learn through struggle, by correcting mistakes. Lessons learned in this way are well embedded in the collective memory of the party, the most thoroughly learned lessons.

Two sources or types of influence have conditioned our development.

Firstly, there are the ideas or lessons that we borrowed from parties in other countries and in other periods – lessons from the class struggle experiences of the international workers’ movement.

Secondly, there are the lessons based on our own experiences in the class struggle here, attempting to build the socialist movement in Australia.

These two influences are not really separate, of course, but posing them that way can help us understand the dynamics involved.

In the early period of our history, there was a particular balance between these two factors. It was a growing up period, one of trying to balance between our raw pragmatism and learning from others – overcoming our youth and inexperience by drawing from the experience of others.

Later, we developed much more self-confidence and were a more seasoned party. We had more experience in the class struggle under our belt and were more able to make use of our own experiences. There was a different balance between the two influences. We still learned from other struggles, but we were more discerning. We became much more capable of thinking things through for ourselves and confident enough to adopt and defend our own political positions, taking responsibility for our own tactical and strategic decisions.

Histories are not “non-partisan” or above class interests, although some claim that they can be. Your political outlook and goals determine the sort of history you write and the facts you select. If your aim is to justify the preservation of the status quo, or to defend a reformist perspective, certain events are stressed. If your outlook is to make a revolution, you look for the key events that will aid Marxist activists in understanding the past, the better to carry out that task.

It is a truism that history is written by the victors. Both popular historical memories and academic history today are influenced, sometimes controlled, by the ruling class. The British ruling-class journal Economist once put it: “Who controls the past greatly influences the present”, not willing to state it quite so baldly as George Orwell did in 1984 – “Who controls the past…controls the future: who controls the present controls the past.” Ruling-class history extols their tradition, their heroes. It blackens the memory of our heroes and downplays change and revolution.

But even within the workers’ movement, which is suspicious of ideological bias from the bosses, working-class history is often determined by those currents ascendant in the workers’ movement at the time: social-democracy, Laborism, or the official Communist parties tied to the leadership of the Soviet Union. These trends were dominant for many decades of the 20th century; they had the resources to propagate their views as the accepted wisdom of the left.

Working-class histories can also be skewed in another way. They can be dominated by those no longer actively engaged, by those who have given up the struggle – the “write your memoirs” brigade. Sometimes this chimes in with the dominant bourgeois mantras – “don’t struggle, it’s hopeless, we tried it, it doesn’t work …” I’ve found that quite a few of the books that focus or touch on the ‘60s upsurge and the anti-Vietnam War campaign and have their origins in a PhD thesis don’t present a balanced picture. Sometimes it may be due to the influence of the academic supervisor, some of whom are ex-Communist Party of Australia and can inject their own selective perceptions. Sometimes it’s built on the existing literature’s selective judgements. Sometimes it reflects prejudices against those who are sticking to the struggle, which is an affront to those who’ve abandoned activism for a career or a book.

This book should provide a long overdue counterbalance to the outright bourgeois attempts at histories of the period, and the histories influenced by the bureaucratic labour movement “left”, the CPA, or the “new left” of the time, such as Students for a Democratic Society.

This book does not attempt to describe fully the broader political history of those years, although the main events, as they provided the framework for our development, are recounted. Similarly, it doesn’t pretend to be a history of the “labour movement”, which some writers restrict to the history of the ALP and the trade union leadership.

This early period of our history is especially important because Resistance came first, before the Democratic Socialist Party or its predecessors. There was no party, as there is now, to back up Resistance. Resistance in effect founded the DSP. Dedicated Resistance activists were responsible for organising the party, producing the first regular publications, providing the revolutionary seriousness and commitment lacking in some of the older, more experienced comrades we were hoping would lead in building a party.

Those early experiences of the central role of youth for our tendency have continued. The leaders and activists of Resistance continued to be the backbone of the party.

This, of course, is in no way an “official” history. The opinions presented are my own. We can draw lessons, but we don’t take a vote on the past. Our members and supporters today were on different sides of past disputes, and would have their own assessments. Moreover, in our ongoing struggle to build the mass revolutionary party we need, there are no permanent allies or opponents; a future mass party will draw in many comrades from many different experiences and currents, including some who have not marched with us for a while.