Speaking at a rally in Florida in May 2019, United States President Donald Trump told his supporters, “We won’t back down until China stops cheating our workers and stealing our jobs. And that’s what’s going to happen. Otherwise, we don’t have to do business with them. We can make the product right here, if we have to, like we used to.”

On June 1, US customs began collecting a 25 percent tariff on $200 billion of more than $500 billion of Chinese goods arriving in US ports annually. Trump is also threatening tariffs on the remaining goods. China responded by increasing its own tariffs of between 5 percent and 25 percent on almost all of its annual $120 billion of US imports.

Perhaps even more significantly, the US added Huawei, the Chinese multinational corporation (MNC), to the Department of Commerce “entities list” with which US companies are prohibited from doing business without departmental permission. Among other things, the ban means Huawei can no longer offer Google applications such as Gmail, Google Maps and Play Store on its phones, nor purchase US- and British-designed microprocessors needed to produce high-end phones and telecommunications equipment. There is widespread speculation that these two issues alone will gravely undermine Huawei’s market position – at least outside of China. The Trump administration has threatened five other Chinese technology companies, including Hangzhou Hikvision, a leading global supplier of security cameras, with inclusion on the entities list.

In doing this, Trump has spread the so called “US-China trade war” well beyond just tariffs. China has responded in kind, announcing its own Unreliable Entities list – which may include companies complying with the US Commerce Department’s bans. This would include some of the biggest and most powerful companies in the world, such as Google and leading microchip companies like Qualcomm, Intel and British-based ARM, which do a considerable share of their global business in China, or companies making products that are assembled in China.

Popular Support for Trump’s Trade War

While the markets are in a spin and neither the terms nor outcomes of this latest stage are clear yet, what has long been clear is the widespread popular support Trump has for attacking China. US Senator Bernie Sanders, who has long advocated a protectionist stance similar to Trump’s, recently attacked rival Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden for being soft on China. He promised a Sanders administration would best lead the U.S. struggle against China, tweeting, “It’s wrong to pretend that China isn’t one of our major economic competitors” and “When we are in the White House, we will win that competition by fixing our trade policies”.iii Supporting Trump’s contention that US manufacturing job losses are principally caused by China, Sanders tweeted, “Since the China trade deal I voted against, America has lost over 3 million manufacturing jobs”. Besides Sanders, Trump enjoys bipartisan support for his trade policies on China.

Pew Research Center’s spring 2018 Global Attitudes Survey asked, “How serious a problem is the loss of US jobs to China?” Some 83 percent of the US-based respondents rated this as either somewhat serious (32%) or very serious (51%). “Somewhat” or “very serious” was also how 82 percent of respondents rated the US bilateral trade deficit with China. Fully 89 percent of respondents said the same about Chinese ownership of US debt. Eighty-eight percent believe it is “better if the US, not China, is the world’s leading power”. iv

Arguably, this overwhelming anti-China public sentiment is fundamentally based in the wildly popular view that China’s economic development is a threat to US hegemony and economic dominance (and by extension also a threat to the rest of the imperialist camp). In a typical and common piece of reportage, economic journalists at the New York Times argued on May 13:

“China has indeed grown in prosperity, leaping into the ranks of what the World Bank defines as upper-middle income countries. Its economy is now bigger than any other country except the United States. Its manufacturing sector is now bigger than those of the United States, Germany and South Korea combined.”v

The same general view of China’s supposed threat to the dominance of the US and other rich countries appears also to be fairly ubiquitous on the left. In a recent article commenting on the trade war in Truth Out, US socialist Ashley Smith characterised the relationship between the US and China as “the central inter-imperial rivalry of the 21st century”.vi

Smith does not even clearly oppose US aggression against China, even while admitting the US is the richer, more powerful country. According to Smith,

“The new socialist movement must adopt a clear and principled anti-imperialist position against both the U.S. and China. We must oppose Trump’s nationalism and protectionism; it will only whip up anti-Asian racism domestically and divide workers in China and the U.S., who share common interests in a struggle against their bosses and their states. We should also oppose the Chinese state.” China “competes as an imperialist power with the U.S. for dominance in the world market”.vii

But is it at all realistic to view China as a rising peer competitor to the United States? Or Chinese competition as the cause of widespread pain to working class communities? Or China as a country that has the potential to rise further into the top ranks of the imperialist hierarchy of nations?

It is hugely convenient for the US capitalist class to present the very real pain inflicted on workers over several decades as essentially inflicted by a foreign enemy (assisted, as Trump says, by that enemy’s feckless domestic lackeys). But left acceptance of the idea of China’s supposed rise as an “imperialist” power risks falling boots and all into what is essentially a national chauvinist dead end. The reality, it will be shown, is that the US will win its trade war against China because US companies – wielding technology developed largely by the US state and organisations it supports – (together with similar companies from the other high income countries) possess an unshakeable control over the international division of labour.

The Apparent Inevitability of China’s Rise

Images of gigantic container ports, angular fast train carriages, modern high rise buildings and warehouses full of neatly stacked steel coils are constantly fed through the capitalist press. These images, which are rarely contrasted with striking images of hugely underdeveloped parts of China’s economy, suggest the view we might take of China’s level of economic development.

To most, China’s rise appears irrefutable, at least at first glance. On World Bank figures, China’s share of world GDP rose from 3% to 15% in just the two decades 1997 through 2017.viii According to the Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis, US manufacturing employment fell from a high of 17.6 million in 1998 to 12.8 million today (up from 11.5 million in mid-2010).ix

It is taken to be self-evident that this collapse in US manufacturing employment is caused by China’s growth as a major manufacturing and assembly location and its corresponding rise in manufacturing employment. It is, of course, a reality that businesses in the US and other imperialist states moved many simple, labour-intensive production processes to China. It is also true that, in other cases, First World companies lost business to Chinese competitors – typically in standardised, ordinary or labour-intensive production processes. These basic facts are the very real material basis for the popular view bolstering Trump’s policy.

However the narrative that sees China’s as a peer competitor with US capitalism, one that challenges the dominance of the US, fails to understand the principal dynamic of the international division of labour. The attraction of cheap labour in China and other Third World countries did not encourage MNCs to move production processes offshore in an indiscriminate way. It encouraged them to move simple, ordinary or labour-intensive processes.

The very selective character of offshoring or “globalisation” means rich country-based MNCs tended to retain sophisticated or less labour-intensive labour processes inside the rich countries. Over time, China and some other Third World countries such as Malaysia and Thailand have increased the number of less simple labour processes they could carry out competitively on the international market.

China, as we are endlessly reminded, has also attempted to develop some more advanced labour processes domestically. Yet the scope and prospects of this policy, and its level of success, are often wildly overstated – while the history of false starts and failures is virtually unknown.

Perhaps most importantly, US and other First World capitals and states have not stood still. Offshoring of simple labour processes already shaped a division of labour whereby low-end labour processes are concentrated in the poor countries (keeping them poor), while high-end labour is kept inside the borders of the rich states. Further, the abandonment or competitive loss of low-end spheres of production freed First World capital to concentrate on continual development of its technological supremacy. These capitals increasingly specialise in sophisticated or more mechanised processes. In doing so, they have increased their overall monopolistic control of the global division of labour, as well as their share of world income.

At the same time, through the development of ever more automated factories, of factory-less research and development companies (like Apple and Qualcomm) and of specialisation on only the specific production processes that are technically new or difficult, the new global division of labour has indeed resulted in a decline in US factory jobs. It is not, however, the result of China’s rise. It flows from the technically new forms in which imperialist domination over the Third World is expressed and reinforced.

China as the Principal Loser in the Trade War

In May 2018 Chinese mobile phone maker ZTE announced it was shutting its factories. The announcement came just weeks after the US government prohibited US companies from doing business with ZTE following an alleged violation of US-imposed sanctions on Iran. The US ban was clearly the cause of the company’s collapse.

ZTE had 74,000 employees at the time and was China’s second largest telecommunications equipment maker, after Huawei. Forbes reported ZTE confirmed it would shut down because “most of its products use American technologies, from high-end 5G equipment to low-end Android smartphones, and that it will be close to impossible for ZTE to redesign new products around the U.S. tech ban”.x As part of ongoing trade negotiations with China, Trump ultimately rescinded the ban – bringing ZTE back to life – after a personal appeal from Chinese President Xi Jinping and an agreement from ZTE to pay US1 billion in fines. In May 2019 Huawei – China’s largest telecommunications equipment company, and its most successful international company – was targeted in almost the same fashion.

Huawei is not the largest Chinese corporation but with sales of $108 billion and profits of $8.8 billion dollars last financial year, it is still one of the biggest companies in the world. It is perhaps the only major Chinese company that competes with the global MNCs as a peer competitor in high value markets. It is likely this is the real reason – and not national security – that Huawei has been singled out by the Trump administration.

Like ZTE, Huawei is facing loss of its critical high technology suppliers, without which it is unlikely to keep producing high-end phones or 5G telecommunications equipment. Huawei bought roughly $11bn in components and services from 1200 US suppliers last year – all will be subject to the ban.xi Leading microchip companies Intel, Qualcomm, Xilinix, Broadcom, Infineon and ARM all suspended business with Huawei following the Commerce Department announcement. In addition British Telecommunications companies Vodafone and EE have both excluded Huawei handsets from their new 5G networks. Smartphone sellers across the world have suspended sales of Huawei’s latest handsets.

Google, also complying with the US sanctions, announced suspension of Huawei’s access to future Android operating system updates – though it has applied for an exemption to the ban. While Huawei would still be able to use the open source version of Android on its phones, it could not use Google applications such as Gmail, Google Maps and Play Store, making it harder to sell phones outside China.

Huawei’s phones rely, for their primary microchips, on both the US-based market leader Qualcomm and Huawei’s fully owned subsidiary HiSilicon, based in China, making it less dependent than ZTE on US parts. However, HiSilicon is itself dependent on foreign technology, in particular ARM, the U.K.-based provider of basic chip designs and California-based software companies Synopsys and Cadence, which are used to produce the blueprints for circuits.xii

While Huawei is believed to have stockpiled supplies of current generation chips adequate for around 6–9 months, and may be able to produce more of the same generation chips under current licensing agreements, the company will likely have difficulty upgrading to new chips. Geoff Blaber, from CCS Insight, told the BBC, “ARM is the foundation of Huawei’s smartphone chip designs, so this is an insurmountable obstacle for Huawei … They’re not going to be able to easily replace these parts with new, in-house designs – the semiconductor industry in China is nascent.”

In their article “American Threat to Huawei’s Chip Maker Shows Chinese Tech Isn’t Self-Sufficient”, Wall Street Journal business writers Kubota and Strumpf suggest, “While other chip makers and HiSilicon’s suppliers shift to future versions of ARM technology or products from the software companies, the U.S. blacklisting will leave HiSilicon stuck with older tools, hindering its ability to compete on the frontiers of chip design and extending the time it takes to develop its products”.xiii

Yuan Yang of the Financial Times reports, “When it comes to telecoms equipment such as mobile Financial Times masts, Huawei relies on logic chips called field-programmable gate arrays (FPGAs) made by US company Xilinx. The other major FPGA suppliers, Intel’s Altera and Lattice Semiconductor, are also US companies … Analysts reckon China is more than 10 years behind in designing high-end logic chips of the kind used in Huawei’s switches and routers”xiv

US attacks on Huawei might not be isolated. The Washing Post reported on May 22, “The Commerce Department is drafting new regulations to limit exports to China of 14 categories of advanced technologies, including quantum computing, robotics and artificial intelligence.”xv

The dependent state of China’s technology companies today has not come about through light mindedness or lack of trying to turn around the situation. China has been attempting to gain semiconductor independence for decades. For example, as Craig Addison wrote in the South China Morning Post last year, “In the 1990s billions of yuan were invested into new semiconductor fabrication lines using technology (legitimately, in this case) transferred from foreign chipmakers, only to find that these ‘wafer fabs’ – that can take two years to build from scratch – were outdated on day one because the state of the art had moved on”.xvi

It’s not that China will not be able to produce smartphones, 5G equipment or other “technology” goods without inputs from the US and other First World countries. What Trump’s ban brings into question is its ability to do that competitively on the world market and especially at the highest end of the world market.

China’s Muted Response

There appears to have been zero discussion in the US press – that this writer can find – about any supposed or feared Chinese responses that involve withholding Chinese technology. Yet we might expect that a rising competitor to US imperialism would have developed at least some technological monopolies of its own, even if not yet on the scale or complexity of the US, Europe or Japan. However, discussion around possible Chinese responses to Trump’s attacks seem to revolve exclusively around non-technological, mostly very weak, possible responses. These are further tariffs, sale of US Treasuries, an embargo on selling rare earth elements and state regulatory obstruction to US companies doing business in China.

During a recent visit to southern China, responding to US attacks, President Xi Jinping urged Chinese people to prepare for difficulties that he likened to a “new Long March” – hardly an optimistic outlook. Notably, Huawei founder Ren Zhengfei strikes similar notes. In a recent interview with Bloomberg, he likened his company to an airplane, now with holes in it, though vowing to work tirelessly at fixing the holes, even if the holes would allow others to catch up.

China now applies tariffs of 5 to 25 percent on $110 billion of its $120 billion in US imports – a lower rate, on average, than the US has so far applied to $200 billion of Chinese imports. $110 billion amounts to less than 7 percent of the $1.7 trillion total US exports for 2018 and is not expected to land a major blow to US expansion. China, by contrast, was already showing signs of slowdown even before the effect of the new tariffs, with many companies moving production to alternative cheap labour locations such as Vietnam or Mexico, or planning to do so. Miao Wei, China’s minister of industry and information technology, told the recent China Development Forum, “The total size of the work force is falling, the labor cost is rising and we are losing our competitive advantage in low-cost industries”.xvii

Given that Chinese tariffs are not expected to have a big impact on the US, several commentators who view China as a powerful competitor with the US have speculated that China might use its $3.1 trillion foreign currency reserves to somehow gain an advantage. However, there is very little China could do with these funds – even if it did wish to initiate a financial war with the USA. The principal problem is that $3.1 trillion is actually not a large foreign reserve in relation to the size of China’s economy. All Third World countries are forced to keep foreign currency reserves as insurance against currency depreciation or other speculative attack. China’s represent around 25 percent of its GDP. This compares to 27 percent for the Philippines, 33 percent for Malaysia and 13 percent for Indonesia.

Moreover, as the New York Times reported, “few see any alternative for China, other than remaining invested in [US] Treasuries. The benchmark 10-year Treasury yield is currently 2.42 per cent, well above the negative yields on equivalent German and Japanese sovereign bonds and still markedly higher than the 1.03 per cent offered on 10-year gilts in the UK.”xviii

China holds just 7 percent of around $16 trillion in total outstanding US Treasuries or 17 percent of foreign-held Treasuries. Even if it did start selling these, it could not blow up the Treasuries market. The likely effect of China’s sell-off would be a tendency to push interest rates higher. Yet the overriding tendency at the moment – due to global fear of economic downturn – is for rates to sink lower. So it’s possible the effect of a China sell-off would hardly even be noticed.

Another speculated silver bullet for China is its global monopoly on the production of so-called rare earth elements – a prospect apparently bolstered by Xi Jinping’s recent visit to a rare earths processing facility in Jiangxi province. But here too, there seems to be no prospect of inflicting serious damage on the US.

Rare earths refers to seventeen chemical elements that are not actually rare. They have also been exploited in California, Malaysia and Australia as well as China. Japan recently discovered rare earths reserves estimated to be adequate to cover domestic needs for 780 years. The Chinese monopoly consists not of a finite natural resource but of most of the world’s operational processing capacity.

Historically the US was the leading producer globally. The reason production shifted to China was because it is a dangerous and environmentally damaging process that produces, among other things, radioactive waste. Chinese capital was willing to win market share by tolerating such costs for returns that were not considered adequate by US or other First World monopoly capital. In doing so China has been providing the materials cheaply – a scenario typical of the Chinese expansion in a whole range of spheres.

However, possessing neither a monopoly over the natural resource nor of technology or productivity in the mining or processing, the current Chinese monopolistic position is vulnerable. There are already three processing plans under construction or planning in the US.xix

While China still controls around 80 percent of the global rare earths market, current US demand accounts for just 4% of China’s rare earth exports. These quantities are considered small enough to circumvent any Chinese attempt at embargo through alternative sourcing, especially via the Mount Weld Mine in Western Australia, which has the world’s largest reserves, or through use of alternatives. Notably the Australian owner of Mount Weld – Lynas Corporation – also outsources environmentally damaging processing to the Third World, in this case to Kuantan in Malaysia, where it’s so-called Lynas Advanced Materials Plant is subject to an ongoing campaign for its closure (and the removal of its radioactive waste to Australia).xx

Chinese attempts to embargo rare earths exports to Japan in 2010, over the Japanese arrest of a fishing boat captain detained in waters surrounding the disputed Diaoyutai/Senkaku Islands, ultimately failed despite Japan’s heavy dependence on rare earths from China and China’s much greater global market share (97%) at the time.xxi While Japan did release the boat captain, it still controls the islands.

Probably most worrying to US capital is the potential for the Chinese state to obstruct the considerable operations of US MNCs inside China. Many US corporations, such as General Motors, make a large part, or even most, of their sales in the Chinese market – dominating many sectors of it, or dominating its high end. Hence they are dependent on Chinese state regulatory approvals, such as environmental approvals, to sell or invest.

Squeezing US corporations out of certain sectors, or simply making their life difficult and more costly through delays, uncertainty and increased regulatory scrutiny and enforcement certainly has the potential to hit US corporate profits, and perhaps make some corporations’ China business unviable. It’s also the case that US retaliation in kind would have nothing like the same impact on China simply because Chinese investment in the US is less significant and has dropped off under existing US state pressures.

Yet the ability or willingness of the Chinese state to roll out such a policy in a wide range of areas critically depends on the capacity of its capitalist producers to replace the roles that US capital is currently playing. Overall, that would tend to be possible for lower technology operations and not high tech. There seems to be little appetite in other advanced countries, such as Japan or Germany, to defy US policy on China. Arguably this is because these rich developed countries have an economic relationship to China similar to the US’s. While selective Chinese harassment of US firms may occur, broad-based hindrance of US capital would likely lower the overall technical level and efficiency of production processes in China.

Chinese ownership of Treasury bonds or rare earth factories hardly seems the favourable terrain of a rising hegemon launching itself against US power. Yet these are the areas where China supposedly wields most power. The perilous position that China is in raises the question of how it is that the second biggest economy in the world, with the largest labour force and the centre of much world manufacturing and assembly and – until recently – the highest levels of GDP growth, could remain so weak in the face of what many view as an ailing US empire.

To answer this question, we have to look beyond the GDP growth figures and ask what is the essential character of the apparently very different types of economic development that have been pursued in China and the US over the last three or four decades.

Monopoly versus Non-monopoly Capital

The essential difference between Chinese capital and that of the US or other rich countries can be characterised as that between non-monopoly and monopoly capital. As seen above, the profitability of companies such as ZTE and Huawei is mediated by their degree of technological capacity. Before looking at how the concept of monopoly versus non-monopoly applies to the international division of labour (below) it is useful to look at how it corresponds to both the profitability of First and Third World corporations and to the income in First and Third World societies.

The characteristic feature of monopoly capital – which is based principally in the rich countries – is higher rates of profit. Non-monopoly, Third World corporations, even very large ones, tend to have far lower rates of profit. These high and low profit rates of the largest corporations also correspond to high and low national per capita income levels in the countries where these companies originate and are based.

The global divide between monopoly and non-monopoly capital is therefore also expressed as the growing global rich-poor divide between countries. While it is popular to think that China and other parts of the Third World are catching up to the rich countries, a look at per capita income data shows this is far from real.

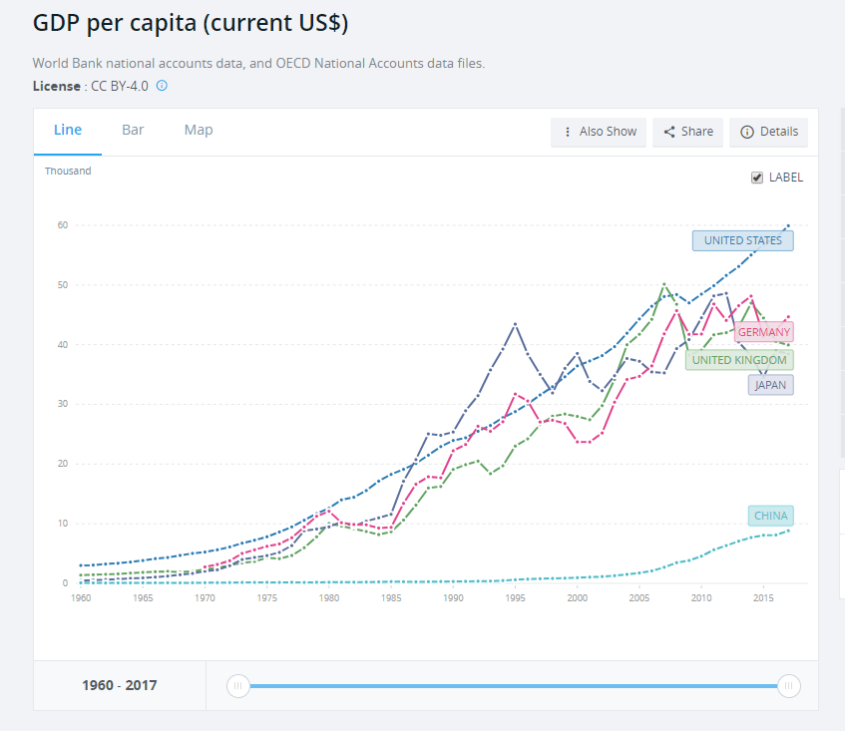

Figure one shows Chinese per capita income is not catching up with core imperialist states. If we take only the period of its most rapid increase (2000–2017) Chinese annual income rose from an average of $959 to $8,827 or $7,868 total rise. Over the same period United States income rose from $36,450 to $59,928 i.e. $23,478. Thus even in the most favourable period for China – when the US economy suffered two recessions and a long depression – aggregate per capita income of US capitalists and workers grew, on average, three times faster than Chinese income. Figure 1 also shows that the divergence between low and high income countries is not isolated to China and the United States. In reality it is typical. The trend of divergence between rich and poor societies holds true for states representing 98.5% of the world population for the period 1980-2015.xxii

Figure 1: GDP per capita (US dollars)

Source: https://data.worldbank.org/

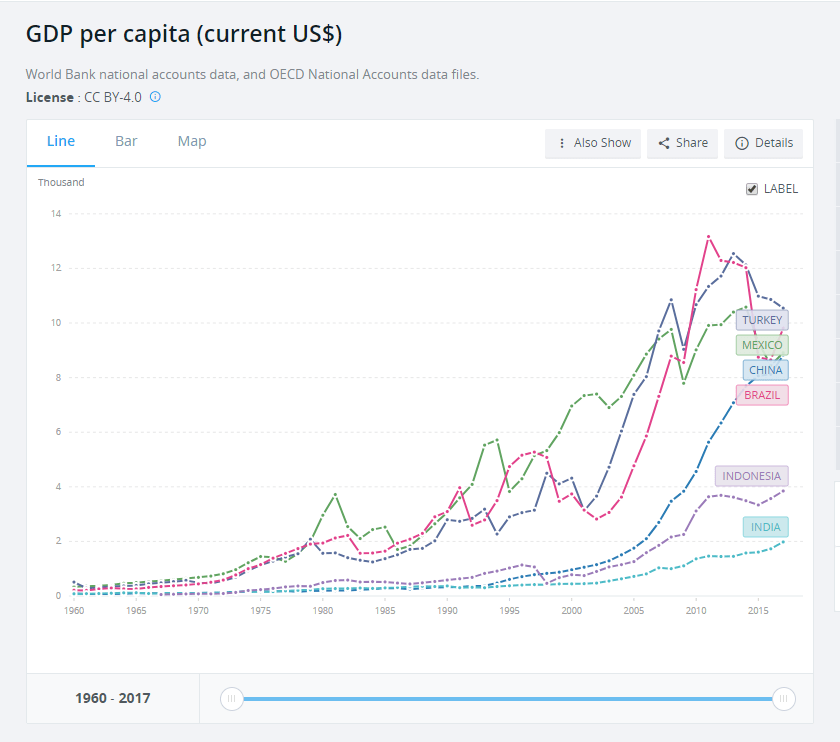

Figure 2: GDP per capita (US Dollars)

China and other large, relatively developed, Third World States

Source: https://data.worldbank.org/

Figure 2 shows the real sense in which China has actually “risen”. By 2017 the large relatively developed Third World states had all converged around the same per capita income level – $8,820 to $10,750. China is the lowest among these major countries (income $8,827). This is less than Brazil ($9,812 – not labelled correctly in the figure). The highest is Russia ($10,749 – not labelled). The chart shows that China has indeed moved above the income level of South Asia (of which India is typical) and most of South-East Asia (represented in the figure by its most important nation, Indonesia). However, it has risen only enough to converge with other relatively developed Third World states – at a level far below that of the imperialist states.

The underlying reason for this is the low profitability of large Chinese capital compared to capitals based in the imperialist core. If we measure the profitability of giant Chinese corporations and compare this with MNCs from the US or other high income countries, we can observe a clear parallel to income polarisation between countries.

Forbes.com publishes data on the largest 2000 public companies globally. This excludes Huawei and a handful of large US companies such as Cargill and Koch Industries, which are private – but still provides a useful overview.

According to Forbes‘ ranking system – which considers volume of sales, profits, assets and market value – Chinese companies make up five of the top twenty companies – positions one, three, four, seven and eight. The other fifteen positions in the top twenty are made up of companies from the USA (11 companies), plus Holland, South Korea, Japan and Germany. The apparent dominance of Chinese corporations on the list – like other indications of China’s size – is frequently understood as powerful evidence of China’s rise.

However, as soon as we ask the website to order the companies according to market value, we get a completely different list. Market value expresses what capitalists thinks the companies are worth and hence the profits one could expect to earn by owning its shares. By market value, the top six positions are all US companies, as are 14 of the top 20. China’s share of the top twenty drops from 5 to 3, while the remaining 3 positions are filled by Switzerland, South Korea and Holland.

Looking at the top fifty companies by market value, we get a similar picture. Forty-two companies are from the high income countries: USA (32), Switzerland (3) and Taiwan, Hong Kong, Japan, Belgium, United Kingdom, South Korea and Holland with one each. Only eight companies come from the Third World – all from China.

If we look at the top 100 companies by market value, the same basic picture emerges again. Of the companies ranked 51-100, 42 are from the rich countries: USA (22), United Kingdom (4), France (3), plus Holland, Germany, Canada and Ireland (2 each) and Australia, Hong Kong, Denmark, Japan and Spain with one each. The remaining eight companies are from China (4), India (2) and one each from South Africa and Saudi Arabia.

There is a striking contrast between China’s apparent domination on -2022282340 Forbes’ measure, which emphasises size, and its relative absence on the market value measure, which emphasises profits. However, market value still measures gross profits and hence includes even relatively low profit operations if they are big enough. If we want to understand the reason for the discrepancy between the two measures we need to look at companies’ profit rates.

Forbes also gives figures for the Return on Assets (RoA) of each company. While far from the only measure of company profitability, RoA at least gives us a general picture of the vast chasm separating almost all large Third World capital from large First World capital. We can see this by taking the biggest 20 companies according to -2022282340 Forbes and comparing their RoA. Arguably, RoA is less meaningful for financial companies. So the table below compiles the top ten non-financial First World and Third World corporations.

Table: Largest Non-Financial Public Corporations’ Return on Assets, 2019 (Billions of US Dollars)

First World Corporations

| Forbes rank | Company | Country | Assets | Profits | Return on Assets % |

| #6 | Apple | USA | 374 | 59.4 | 15.9 |

| #9 | Royal Dutch Shell | Netherlands | 399 | 23.3 | 5.8 |

| #11 | ExxonMobil | USA | 279 | 20.8 | 7.5 |

| #12 | AT&T | USA | 532 | 19.4 | 3.7 |

| #13 | Samsung Electronics | South Korea | 304 | 39.9 | 13.1 |

| #15 | Toyota Motor | Japan | 466 | 17.2 | 3.7 |

| #16 | Microsoft | USA | 259 | 33.5 | 12.9 |

| #17 | Alphabet (Google) | USA | 233 | 30.7 | 13.2 |

| #18 | Volkswagen | Germany | 554 | 14 | 2.5 |

| #19 | Chevron | USA | 254 | 14.8 | 5.8 |

| 3654 | 273 | 7.5 |

Third World Corporations

| Forbes Rank | Company | Country | Assets | Profits | Return on Assets % |

| #22 | PetroChina | China | 354 | 8 | 2.3 |

| #35 | Sinopec | China | 233 | 9.5 | 4.1 |

| #40 | Gazprom | Russia | 306 | 18.9 | 6.2 |

| #50 | Petrobras | Brazil | 222 | 7.1 | 3.2 |

| #52 | Rosneft | Russia | 191 | 8.7 | 4.6 |

| #59 | Alibaba | China | 134 | 10.3 | 7.7 |

| #71 | Reliance Industries | India | 125 | 5.6 | 4.5 |

| #74 | Tencent Holdings | China | 105 | 11.9 | 11.3 |

| #80 | China State Construction Engineering | China | 271 | 5.8 | 2.1 |

| #94 | Evergrande Group | China | 274 | 5.8 | 2.1 |

| 2215 | 91.6 | 4.1 |

Source: http://www.forbes.com/global2000/list/

As can be seen, First World MNCs achieve RoA almost double that of Third World corporations. If Third World capital was catching up, it would need to achieve a higher return on its investments than its much larger competitors, not a far lower return. This is no fluke of statistics. The same was true when this writer analysed both the Forbes Global 2000 and the Fortune Global 500 lists for 2017. For example, comparing the top 15 non-financial corporations from both rich and poor countries on the Fortune list gave a return on assets of 4.7% for First World corporations and just 2.7% for Third World companies that year.xxiii

The reality of Chinese giant companies – and those of other Third World countries – is that, overwhelmingly, these are domestic monopolies with few if any international operations. While the sheer size of China’s economy means it can sustain a high number of very large companies, the degree of their profitability (at least on average) is mediated by the weak competitive position of Chinese capital within the international division of labour.

This phenomenon is not at all unique to China (except for size). If we keep looking down the list for Third World companies, say in the top 200, top 500 and so on, what is noticeable is the appearance of companies from all major the Third World economies. For example India – because it too has a gigantic population – has ten companies among the largest 500 global companies and twenty-five in the largest 1000. This is despite having per capita income just 3.3 percent of the USA! Other smaller, though slightly richer, Third World countries similarly support several large companies. Turkey, for example, has seven companies in the largest one thousand, South Africa has nine, Thailand eight, Indonesia and Mexico five, Malaysia four, Colombia three and so on.

Typically these companies are nationally monopolistic oil, electricity, telecommunications or banking corporations. For the bigger or richer Third World countries, other domestic monopolies, such as steel and cement companies or retail and media companies can grow quite big and also appear on the list. However, with just a handful of exceptions, there are almost no internationally competitive, globalised companies comparable with First World MNCs (even embryonically) – at least not in the important economic spheres. As Nolan points out, building up a large domestic business in a period of rapid national expansion is one thing, building an internationally competitive company is another.xxiv

There are, however, some spheres in which Third World companies – and Chinese companies in particular – are globally competitive. The problem is that this occurs almost exclusively in the least profitable, lowest echelons of the global value chain. The classic case, perhaps, is Chinese computer maker and technology company Lenovo, headquartered in Beijing. Lenovo has grown to be world’s largest seller of personal computers (by units) since it acquired IBM’s personal computing business in 2005.

While the sale of such an iconic brand to a Chinese company was hyped at the time as a sign of China’s rising power, subsequent years at Lenovo suggest otherwise. Worldwide PC shipments have been in decline since 2011 and, at its low end, prices have dropped, as PC technology becomes more commonplace. Lenovo, while holding a leading market share, successfully defended a turf that was both shrinking and becoming lower value. The company’s annual profits for 2018 were $511 million according to Forbes, with a RoA of 1.6%. That compares to IBM, which made 17 times more profits: $8.6 (RoA 6.6%) by moving into higher end labour processes.

It is clear from the above data that China has not reached the economic development level of the US and other First World countries; otherwise, its companies would be able to demand higher prices on the world market for the commodities they produce. The more serious argument put forward by China boosters is not that China has caught up, but that it can catch up or will catch up. The least serious version of this argument consists essentially of maths sums. One can calculate the rate of China’s GDP growth over the last two or three decades and assume this will continue into the future. There is an obvious problem with the maths, because it ignores the statistical bias of percentage increase to the country starting from a low base. However, if we put down the calculator and look at the history, the maths method completely falls apart.

Rapid GDP growth was not a phenomenon unique to China but a general phenomenon among a number of very low income East Asian countries in the neoliberal period. It is a general phenomenon of the 35 years 1980–2015 that poorer Third World countries grow faster than richer ones – even if China represented a highly exaggerated case.xxv Fast growth occurred principally through farmers moving into the cities and taking up factory or other jobs. However, China has already largely carried through that transition. In doing so it has already moved, as mentioned, from among the lowest income countries to among the top, large Third World countries. If we take the example of the large Third World countries with the highest income at the beginning of the neoliberal period (1980) – Argentina, South Africa, Brazil and Mexico – and look at their rate of income growth over the neoliberal period, it was very slow – almost stagnant.xxvi That is the prospect China now faces if it cannot bring about a different development model to that at which it has been successful thus far.

World Division of Labour Between Monopoly and Non-monopoly Capital

Of course the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is aware of the problem – the so called “middle income trap” – which in reality occurs at the quite low income levels of high-end Third World countries like China, Mexico and Brazil. The CCP is attempting to overcome the roadblocks by upgrading China’s technological capacity, especially through the flagship Made in China 2025 policy framework. While the theory is very simple – nations must technically upgrade in order to continue to raise incomes – the practice is fraught.

It would be possible to move up the ranks of the global division of labour if China could develop a scientific base and internal social organisation equal or superior to that of US imperialism. This is of course possible in the abstract. However, the policy of the CCP cannot be abstract but must correspond to the realities of an imperialist world system. It has chosen to attempt to develop Chinese society via a path of capitalist development integrated into the imperialist world market. Therefore it is the concrete realities of this market and social production processes that underlie it that Chinese capital must navigate.

The polarisation of money income manifests the underlying social productive polarisation: the division of the world into spheres of high and low labour productivity, technology, scientific development and social organisation. The world division of labour is also divided between high-end, most sophisticated labour processes monopolised within the imperialist core and low-end or ordinary labour processes, which are distributed to the Third World. China is not an exception to this rule but the major example of it – the most successful developer of ordinary labour processes.

Technical polarisation of the global division of labour means that the overwhelming bulk of labour processes carried out in the low income countries, including China, consist of basic or ordinary labour. For this reason the social demands on most Chinese workers, technicians, scientific workers etc. do not involve systematic thinking and problem solving in the most advanced available manner. From this material-social base, the cultural development of the society can never be as advanced as that of imperialist societies, which monopolise humanity’s social and scientific advances for themselves.

The imperative of capitalist profitability ensures that no true assault on the commanding heights of world scientific development and the division of labour can be launched from a low material-social base. Storming the commanding heights would involve competition with the most advanced capital for the most advanced labour processes – a competition that a less developed or, as Che Guevara described it, ill formed capitalist social formation, is ill suited to carry out. This is why frontally challenging imperialism will not deliver the highest available profits to Chinese capital. Challenging imperialist monopoly at its margins is necessary to make profits. Yet a frontal challenge risks complete debacle.

For this reason, the interests of Chinese capital will never form the social basis for a full blooded assault on imperialist dominance (even ignoring the politically perilous level of working class social mobilisation that would be required for an underdeveloped society to wage such a serious campaign against imperialist supremacy). Chinese capitalism is not and can never become the revolutionary social force that can storm the heavens of US power.

What could conceivably happen is that more areas of the labour process that are presently dominated by the imperialist societies and hence subject to monopoly pricing, could be wrested from them and become the domain of Third World production – the same thing that has already happened, for example, in low grade steel production and other industrial processes. The same may be true several years from now for the production of basic automobiles. If the proportion of necessary world labour coming under the control of non-monopoly capitalists increases, or the degree of imperialist technical superiority in high-end labour is reduced (and thereby the degree of imperialist monopoly in these is reduced), then the gap between Third World and First World income could conceivably narrow relatively – even as the overall polarisation remains robust. However, a narrowing gap between the two camps is the opposite result to the overall outcome of neoliberal period (1980–2015) and far from inevitable.

The gap cannot close entirely because it manifests the basic structure of the world market – the development of both monopoly and non-monopoly capital. The social and market polarisation between monopoly and non-monopoly capital, its reflection in the technical polarisation of labour, is the reason income inequalities manifest not as random variations, or on a spectrum, but mostly as two principal poles – rich and poor capitals, rich and poor states, rich and poor societies.

There is no ladder from ordinary to advanced labour accessible to Third World societies – except with the cooperation of imperialist core states. Every Third World society is continuously pulled back into the mundane routine of ordinary labour for the simple reason that this is where their capitalists can make money. There has been no change in that basic social structure of imperialism over the last several decades. Only the technical composition of what constitutes high and low-end labour has evolved in tandem with the general development of the human labour process itself.

To the question “can Chinese capital compete with US companies?”, there is a simple answer: “yes and no”. Yes, it can and does successfully in ordinary labour processes. Ordinary labour can be carried out by any or many average, competent capitals, which means no big advantage is imparted by a country’s higher level of scientific development. This type of labour process is most suited, under imperialism, to the Third World, where labour is cheaper. On the other hand, in labour processes in which the benefit of cheaper labour is less important than proximity to scientific research, availability of specialised skills, specialised state support etc., Chinese capital typically cannot compete with capital from the imperialist core.

However, success even in cutthroat competition for control of low-end labour processes is not the same thing in any sense as China developing into a similar type of economy to the US. On the contrary, out-competing, First World MNCs in low-end processes actually forces the rich countries to shape and consolidate their specialisation in the highest end, most monopolistic labour.

The massive shift of manufacturing to China in the neoliberal period was part of a general global trend (at least until recently) of shifting ordinary and low-end labour, as well as environmental destruction, to the Third World. As Bieler and Lee point out: “China is the assembly platform of global capital” and “is predominantly based on cheap labour, necessary for assembling the various parts into final products for export to North American and European markets”.xxvii

The increasingly sophisticated and hierarchical world division of labour is principally orchestrated by the leading MNCs that profit most from it. According to Nolan, “After the 1970s the world economy entered a new phase of capitalist globalization” which “witnessed massive asset restructuring, with firms extensively selling off ‘non-core businesses’ in order to develop their ‘core business’ and upgrade their asset portfolios”.xxviii

It is not the case that MNCs have cashed in on a quick dollar by forfeiting their leadership position in the long term. They have jealously and successfully guarded their control of the key processes within the international division of labour.

Upward specialisation occurred in the US throughout the neoliberal period. As Schwartz wrote, “large investments in production of durable goods” in the US from 1991 to 2005 outweighed loss of investment in non-durables: “leathergoods, textiles and clothing, and foods and beverages that combined account for just ten percent of manufacturing gross fixed capital formation, saw absolute declines. On the other hand machinery and equipment, transportation equipment, and electrical and optical equipment, combining to make up 40 percent, saw relative increases.”xxix Today common “durable goods” such as home (though not commercial) refrigerators, air-conditioners or washing machines are increasingly the domain of Chinese capital (at least in their final assembly). However, once again this hardly means the US companies that formerly occupied this space – like General Electric – have stood still. They have moved up.

Brenner observed the same phenomenon in Japan. From the time of the Plaza Accord, Japanese capital sought “to focus domestic production in Japan ever more exclusively on the highest tech lines by relying on the country’s highly skilled but expensive labour force, while sloughing off less advanced production to East Asia”.xxx

For Steinfeld, “Chinese specialization in manufacturing assembly has facilitated not only US but also Western European and Japanese specialization in something much more difficult to replicate: knowledge creation and invention.”xxxi “The incumbents – global lead firms – are hardly stationary, and in many cases have completely transformed themselves.”xxxii

Steinfeld’s work in particular demonstrates one new aspect or at least emphasis of the global division of labour as it developed in the neoliberal period – the so called ‘fine slicing’ of various sectors, or what Marx called “branches of production”, into their respective labour components. The purpose has been to divide distribute the various labour processes according to the relative degree of labour sophistication among monopoly and non-monopoly capitals. “Fine slicing” allowed imperialism to achieve a higher degree of concentration and specialisation on highest end labour processes.

Steinfeld says, “Whether for aerospace or apparel, we can conceive of some activities within their respective industry supply chains that are standardized and commodified, and other activities that are highly proprietary”. Industrial sectors that previously existed as a more or less single whole organised by one or more monopoly firms through vertical integration have subsequently been broken up and reorganised – at least in ownership terms – along lines determined by the degree of complexity of each production process.”xxxiii

Steinfeld’s seminal paper was published fifteen years ago, so it could be argued that it has gone out of date. However, it is easy to find contemporary examples of the same phenomena he describes, and they exist right at the heart of China’s efforts to upgrade. One critical aspect of the Made in China 2025 policy is a continuing push at commercial aerospace production through the Commercial Aircraft Corporation of China (COMAC). Headquartered in Shanghai, COMAC is directly controlled by China’s Cabinet, reflecting its national importance. COMAC has so far invested around $10 billion to develop the C919, a mid-sized passenger jet intended to compete with global duopoly of Boeing and Airbus in that line of production. COMAC’s enormous investment includes facilities and personnel spread over more than 110 buildings.

The test flight of the first prototype C919 passenger plane took place three years behind schedule in May 2017, while the second prototype was tested a further three months behind schedule in December 2017.xxxiv This compares to a monthly production of twenty commercial planes at Airbus’ Chinese assembly plant alone and Boeing’s 2016 sales to China of 116 aircraft. The C919, which uses long-established technologies, is considered unlikely to match the performance of Boeing’s and Airbus’ mid-sized commercial planes already in operation, let alone of their next generation planes already under development.

COMAC may not go bankrupt anytime soon, due to guaranteed orders by Chinese state-linked domestic airlines and state financial backing. However, so far, orders for the plane have come almost exclusively from Chinese state-owned companies and General Electric (GE) – which stands to gain from its involvement in the project, and has ordered twenty. If such a trend were to continue, the company would begin to look like an aerospace version of the numerous other large, hardly profitable domestic monopolies identified.

The C919 relies on collaboration with US industrial giants GE and Honeywell for high technology components. The New York Times reported, “In addition to the avionics, G.E. has also collaborated on the engines, while Honeywell is providing auxiliary power systems, wheels, brakes, fly-by-wire controls and navigation equipment”. The paper reported, “Honeywell expects $15 billion in sales to the C919 program during its 20 or more years of production”.xxxv Thus even if the Chinese Cabinet and COMAC are successful in establishing their own mid-sized aircraft as an international competitor to Boeing and Airbus, this will not guarantee that most of the profits from the aircraft’s sales will stay in China. Moreover, the mid-sized commercial jet market is a less lucrative and lower tech than large jets.

But it is not only leading technology companies like Honeywell and G.E. that benefit from their operations in China. According to Harley Seyedin of the American Chamber of Commerce in South China, “The reality is that our companies are continuing to operate in China successfully, they continue to make profits, substantial profits, they have to continue operating in China to maintain and capture additional market share”.xxxvi

Possibly the only major exception to this picture, or at least the most important exception, is, or was, the Huawei. The company’s central management is Chinese. However, its significant research and development expenditures span much of the imperialist world. According to company material, “In 2015, approximately 79,000 employees were engaged in R&D, comprising 45% of our total workforce”.xxxvii Huawei’s strategy has not been to develop world-beating R&D in China. Rather, it has funded research and development centres in China, the United States, Germany, Japan, United Kingdom, Russia, Israel, Turkey, Canada, India, Belgium, Finland, France, Brazil and other states.xxxviii

This is consistent with a strategy in which leading MNCs maintain a global network of R&D facilities alongside global networks of production facilities. Globalised R&D typically mimics the same hierarchical and polarised structure of the globalised division of labour more broadly. Third World R&D will cheaply carry out standard processes, while the imperialist core is used for high-end research.

Even if Huawei’s international businesses can survive Trump’s onslaught, its future as a leading global firm is hardly secure. Take the example of smartphones. Huawei quickly rose as a smartphone maker, surpassing Apple in sales volume (though not revenue) and trailing behind only Samsung as the highest selling mobile phone maker in the world.

Yet what this rise reflects is not only the advance of Huawei’s technical capacity but also the so called “maturing” of the smartphone market. As the technology “matures”, i.e. becomes more commonplace, smartphone design and assembly have begun to cease being areas of well above average profits or rapid sales growth. iPhone’s loss of market share (though still dominating the top end of the market) has not resulted in any proportionate overall reduction in Apple’s profit.

Compared to Huawei’s $8.8 billion, Apple made $59.9 billion profit in 2018. Apple’s business is not threatened by Huawei – only its phone business is (or was), and this only over the medium term. If Apple were unable to move into new lines of business, and remained forever dependent on iPhone sales, then it would lose its dominant position as the world’s most profitable company. However, the company has long been expanding higher end “services” businesses. As Ewan Spence put it, “Hardware sales, especially of the iPhone, need to be leveraged in the short- and medium-term as Apple looks to move to a services first business model”.xxxix

That transition has already begun, very successfully, according to Katy Huberty from Morgan Stanley, who estimates Apple received $37.2 billion in services revenues in 2018 for things like Apple Music, applications and cloud computing. Huberty estimates Apple will achieve 20% annual service growth over the next five years.xl Of course this upgrading and moving into newer, higher technology areas is not only Apple’s trajectory, but is the general tendency of monopoly capital and the key to its ongoing supremacy despite the progress of capitalist production in China and other Third World countries.

What is the Trade War Really About?

Nothing in Trump’s policy indicates China is some kind of existential threat to US hegemony. To China boosters, the very existence of economic conflict between the US and China seems to prove their view of China’s rise. However, this is not the case any more than the existence of conflict between workers and their boss proves they stand on an equal footing, or are just the same thing.

Imperialist core capital has historically driven extremely hard bargains against even the weakest Third World capital. The “trade war”, which is really an economic attack on China by US imperialism, is about the distribution of the value brought into the world economy by Chinese labour. No Marxist (besides Harveyxli) argues that Chinese capital is a net appropriator of value created by US, British or other First World workers.

The battle being waged between US and Chinese capital is over the degree to which value created by Chinese labour (and therefore Chinese capital) is appropriated by First World capital and US capital in particular. Sections of US capital evidently believe they can achieve better terms, i.e. extract a greater proportion of Chinese value, by embarking on an economic war against China – even if there are different ideas about the best method of war, or how much of a war is desirable before accepting a truce.

Yet, not all aspects of Trump’s policy reflect US capitalists’ specifically economic interests. Some aspects reflect their broader political interests and also the political interests of the Trump White House. After all, Trump can hardly sell a trade war to US workers purely on the basis of benefit to US corporations. He must talk mostly about jobs, and hence emphasise the trade balance and currency levels – even if these are not the key issues for the most powerful sections of US capital.

Since China joined the World Trade Organisation two decades ago, compared to other Third World states, it has enjoyed considerable advantages in negotiating the terms of its own exploitation: the size of its cheap, trained and educated labour force; its relatively well-developed and centralised state apparatus (a historical product of the Chinese masses’ defeat of imperialist political power in China after World War Two); and the size of its domestic market.

As seen, the primary beneficiaries of Chinese workers’ gigantic contribution to world labour have been the US and other imperialist countries. Yet these relative strengths of the Chinese state also coincided and combined with the runaway profits bonanza of cheap labour globalisation during the neoliberal period. In this historical context, Chinese capital was able to use its unique position as the centre of world labour to technically upgrade relatively rapidly compared with other Third World states. The degree of its success is reflected in China’s “rise” from about the income level of India in 1980, to a level today on a par with Mexico and Brazil.

However, since around 2011 cheap labour globalisation has ceased to be principal driving force of above average profits in the world economy. While many companies still rely on cheap Third World labour, and new instances of offshoring will continue (as was already the case prior to the neoliberal period) this is no longer the characteristic driver of economic expansion that it was.xlii In 2019 a greater portion of imperialism’s cheap labour needs can be provided by other Third World societies, giving imperialism a stronger hand to play off the various non-monopoly producing countries against each other.

Of course the Chinese domestic market is still crucial for imperialism to dominate, but it is no longer so rapidly expanding. Unless a radical technological upgrade is successful, the Chinese market will decline in relative importance to the same extent that China’s labour contribution falls as a proportion of total world labour. These weaknesses are counterbalanced by the considerable upgrading that sections of Chinese capital have achieved.

In the new situation, US capital today, or sections of it, are looking to reconfigure the terms of its engagement (exploitation) of China to better reflect its new strengths, weaknesses and needs. It’s not that the major US capitalists face competitors in China capable of defeating them. Rather, they face competitors more able to squeeze certain aspects of the monopolies’ overall dominance and reduce their profits for certain, particularly low-end, less profitable operations and take some market share at the margins.

This is reflected in Trump’s repeated refrains about China “stealing” US “intellectual property” and demands for a Chinese crackdown. What US capital seeks is not legal protection to artificially (politically) forestall the collapse of its tottering dominance over the labour process – although that is likely the case for marginal, individual capitals or sectors. Rather, the dominant sections of US capital seek legal protections that will increase the projection of their technological dominance. Greater legal protection extends the period of time that above average profits can be secured for a given new labour process, product, etc. by slowing competitors’ adoption of it.

Even the complete removal of legal protections would not end the ability of US capitalists to make above average profits on the basis of technological innovation simply because US capital is more technically advanced. If China were in fact developing its own world-beating technologies – the US state would not be demanding strict intellectual property laws; it would be busy trying to copy Chinese innovation.

The other principal aim of the Trump administration is winding back Chinese state subsidies for large state-owned enterprises (SOEs – many of which also have a large degree of private ownership). This reflects another advantage China does possess (at least compared to other Third World societies). As the largest Third World state, and one with a relatively strong state apparatus developed during the Chinese revolution, state subsidies for otherwise uneconomic producers are a key way that Chinese capital is able to compete globally. In doing so it undermines imperialist profitability in competing sectors by undercutting them on price. Yet Chinese state subsidies also increase the profitability of other branches of the imperialist economy, and potentially its overall profitability.

By subsidising and cheapening products, the Chinese state (and ultimately workers) in effect subsidise cheap inputs to the businesses that purchase these commodities. To the extent subsidised products are utilised by First World capital, this is essentially another form of offering Chinese labour cheaply on the world market. Chinese state organisation of subsidies allows China’s cheap labour advantage to be concentrated and shifted from the most labour intensive industries like textiles to higher rungs of manufacturing.

Once we remove the perception that China’s current technological level is a temporary phase in some sort of long march of inevitable transition to dominance, it becomes clear how devastatingly imperialism is plundering China, East Asia and the Third World. All of the burdens taken on by Chinese workers, all of the terrible environmental devastation, dispossession of farmers, separation of working parents from their children and many other injustices and crimes, are not sacrifices in aid of Chinese capitalism’s coming global triumph. They are the sacrifices of China’s success as Third World capitalism par excellence, as the number one provider of good, cheap products to the imperialist economies.

The sooner imperialist exploitation of China is recognised by Marxists and others on the left, the sooner it will be possible to start working towards building international solidarity with China and other Third World struggles. The surest way to break any possibility of Chinese workers trusting and looking for unity with working people in the United States and the other imperialist countries is to swallow the propaganda that China is fast becoming an imperialist power. The Chinese working class knows that it is not. The imperialist world’s workers, so far, do not.

i Atkinson, Rob, president of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (USA) cited in Lynch, David, J. (2019) ‘How the U.S.-China trade war became a conflict over the future of tech’, Washington Post, May 22

ii Yang, Yuan. (2019) ‘How Trump blacklisting affects the inside of a Huawei smartphone’, Financial Times, June 3.

iii Smith, Ashley. (2019) ‘Deal or No Deal, the Rivalry between the US and China Will Intensify’, Truthout May 22.

iv Devlin, Kat. (2018) ‘Americans leery of China as Trump prepares to meet Xi at G20’ Pew Research, November 30.

v Swanson, Ana and Bradsher, Keith. (2019) ‘U.S.-China Trade Standoff May Be Initial Skirmish in Broader Economic War’, New York Times, May 13.

viii World Bank. (2019) ‘databank’, see databank.worldbank.org, accessed May 2019.

ix Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis. (2019) ‘all employees manufacturing, see https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/MANEMP accessed June 2019.

x Su, Jean Baptiste. (2018) ‘China’s ZTE Shuts Down After U.S. Tech Ban over Iran Sales’, Forbes, May 9.

xi Unknown. (2019) ‘Huawei warns ban set to hurt 1,200 US suppliers’, Financial Times May 29 (Pay Wall).

xii Kubota, Yoko and Strumpf, Dan. (2019) ‘American Threat to Huawei’s Chip Maker Shows Chinese Tech Isn’t Self-Sufficient’, Wall Street Journal, June 2; see also Unknown. (2019) ‘The technology industry is rife with bottlenecks’, The Economist, June 6.

xiii Kubota and Strumpf. (2019).

xiv Yang. (2019).

xv Lynch, David, J. (2019) ‘How the U.S.-China trade war became a conflict over the future of tech’, Washington Post, May 22.

xvi Addison, Craig. (2018) ‘China reliant on US core technology for some time, but so is the world: America’s unassailable lead in semiconductor manufacturing is the dividend from over 50 years of research and development’, South China Morning Post, July 4.

xvii Bradsher, Keith. (2019) ‘One Trump Victory: Companies Rethink China’, New York Times, April 5.

xviii Politi, James, Wong, Sue-Lin and Edgecliffe-Johnson, Andrew. (2019) ‘US Companies Step Up Response to Donald Trump’s China Ultimatum’, Financial Times, May 23.

xix Johnson, Keith and Groll, Elias. (2019) ‘China Raises Threat of Rare-Earths Cut off to U.S.’, Foreign Policy, May 21; see also Lynch, David, J. (2019) ‘China hints it will choke off U.S. ‘rare earths’ access. But it’s not that easy.’, Washington Post, June 10.

xx greenleft.org.au/content/malaysia-australian-corporate-polluter-lynas-told-remove-radioactive-waste ; savemalaysia-stoplynas.blogspot.com/ ; http://www.facebook.com/groups/stoplynas/about/

xxi Gholz, Eugene. (2014) ‘Rare Earth Elements and National Security’, Council on Foreign Relations; see also Barret, Eamon. (2019) ‘China’s Rare Earth Metals Aren’t the Trade War Weapon Beijing Makes Them Out to Be’, Fortune, May 29.

xxii King, Samuel T. (2018) ‘China and the Third World are not “catching up” to the rich countries’, Labor and Society, 21.

xxiii King, Samuel T. (2018) Lenin’s Theory of Imperialism Today: The Global Divide between Monopoly and Non-Monopoly Capital, PhD dissertation, available at http://vuir.vu.edu.au/37770/

xxiv Nolan, Peter. (2012) Is China Buying the World?, Cambridge, Polity.

xxv King. (2018) ‘China and the Third World are not “catching up”‘; King. (2018) Lenin’s Theory of Imperialism Today.

xxvi King. (2018) Lenin’s Theory of Imperialism Today, p39.

xxvii Bieler, Andreas and Lee, Chun-Yi, (2017) ‘Chinese Labour in the Global Economy’, Globalizations, 14, 2.

xxviii Nolan. (2012), p16.

xxix Schwartz, Herman M. (2009) Subprime Nation: American Power, Global Capital, and the Housing Bubble, Cornell University Press, p123.

xxx Brenner, Robert. (2002) The Boom and the Bubble: The US in the World Economy, Verso, p116.

xxxi Steinfeld, Edward S. (2010) Playing Our Game: Why China’s Rise Doesn’t Threaten the West, Oxford University Press, p18 and p75.

xxxii Steinfeld, Edward, S. (2004) China’s Shallow Integration: Networked Production and the New Challenges for Late Industrialization, World Development, 32, 11, p1983.

xxxiii Steinfeld. (2004), p1983.

xxxiv Reuters Staff, (2017) ‘Second Prototype of China’s C919 Jet Conducts Test Flight: State TV’, Reuters, December 17.

xxxv Bradsher, Keith. (2017) ‘China’s New Jetliner, the COMAC C919, Takes Flight for First Time’, New York Times, May 5.

xxxvi

Politi, Wong and Edgecliffe-Johnson. (2019).

xxxvii Huawei.com (no date) ‘Research & Development’, Huawei.com, accessed January 2018.

xxxviii Sekiguchi, Waichi. (2016) ‘Huawei to Set up R&D Base in Tokyo’, Nikkei Asian Review, November 26.

xxxix Spence, Ewan. (2019) iPhone Profits Will Crash If China Seeks Huawei Revenge, Forbes.com, May 27.

xl Wuerthele, Mike. (2018) Apple’s services will grow to over $100 billion per year in 2023, says Morgan Stanley, appleinsider.com, November 8.

xli Harvey, David. (2014) Seventeen Contradictions and the End of Capitalism, UK, Profile, p239.

xlii Reshoring Initiative. (2016) ‘Data Report: The Tide Has Turned’, reshorenow.org; UNCTAD. (2017) Trade and Development Report 2017, United Nations, pp. ix–xi and p50; UNCTAD (2013) World Investment Report, 2013, pp. 26–29; King. (2018) Lenin’s Theory of Imperialism Today, pp. 207–210.