[This is the third article in a three-part series by Sam King published by Red And.]

In the previous article in this series it was argued that China is not imperialist in the Marxist sense because its capitalist class is not able to capture, in a widespread way, value that is produced by workers in other countries. That privilege is held only by the capitalist classes of the rich countries such as Australia, the United States, Japan, South Korea and the countries of Western Europe. It is also the reason these countries are rich and China is not.

This then poses the question of, what then is China? Or more accurately, how can we accurately characterise Chinese capitalism? This question is posed especially sharply because many attributes of Chinese policy, such as its military spending and its diplomacy, are presented in the capitalist press of the rich countries, as the most dangerous and aggressive imperialism. There is also widespread agreement among socialists and others on the left with the false narrative that China now poses a threat to the continued global hegemony of the United States.

Arguably this almost ubiquitous false view is based on a failure to develop a concrete analysis of the specific character of Chinese capitalism and of its relationship with the rich countries. This relationship is determined, in the last analysis by the concrete roles that Chinese capital (and the labour it employs) and rich country capital (and its labour) occupy within the global division of labour that makes up world-wide production.

Many socialists falsely assume that the development of Chinese capitalism is the development of fundamentally the same thing – i.e. capitalism – as exists in the imperialist societies. From there it is assumed that this means China will necessarily develop as a rival sooner or later.

It is true, in abstract, that all forms of capitalism are fundamentally the same – i.e. they are based on the class exploitation of workers. However, if we wish to understand power dynamics between different capitalist societies today – that have gone through completely different historical transformations and at different times – it is necessary to specify the nature of their interactions and understand what determines and limits the types of interactions that are possible.

Lack of a concrete analysis, and the assumption of sameness, leads to the proliferation of quantitative comparisons with which many readers will be familiar: the size of GDP, the number of troops or war machines, the number of engineering graduates, the size of certain companies and so on. These gross figures are used to suggest China’s power is now equal or greater than that of the US and has already surpassed smaller countries like Australia, Japan and every other rich state.

It is true that Chinese economic development this century has been remarkable, especially since joining the World Trade Organisation in 2001. Chinese production has fundamentally altered international trade and investment patterns. In a certain sense, it is not without basis to say that “China has been on the rise”. The question is, in what sense?

Many of those arguing China is “rising” as a rival imperialist power seem simply to express that something big is happening, but only guess or infer what it might be. Typically guesses about future dominance are based on China’s past rapid GDP growth. The assumption is that this will continue into the future due to some sort of unstoppable “momentum”. This impression is reinforced daily by unopposed reports in the capitalist mass media by self-proclaimed “experts”, such as Stan Grant. That China is imperialist has become so much a part of “common sense”, that to even question the idea is considered a little odd.

But if we wish to understand what future outcomes might really be possible, we need to understand the actually relationship between China and the imperialist countries. The first step is to put China’s capitalist expansion in context.

It is not accurate to imagine that, for example, China’s increased share in world trade and income has been principally at the expense of the imperialist states. As shown in the first article of this series What is Imperialism?, the rich, imperialist states benefited handsomely from the expansion of capitalist production in China from the 1980s. Much of that expansion was directly organised by the imperialist corporations themselves, either through their ownership of Chinese factories or by placing orders with Chinese suppliers. There are also cases where Chinese companies out-compete imperialist companies, but this tends to happen only in very specific circumstances that are outlined below.

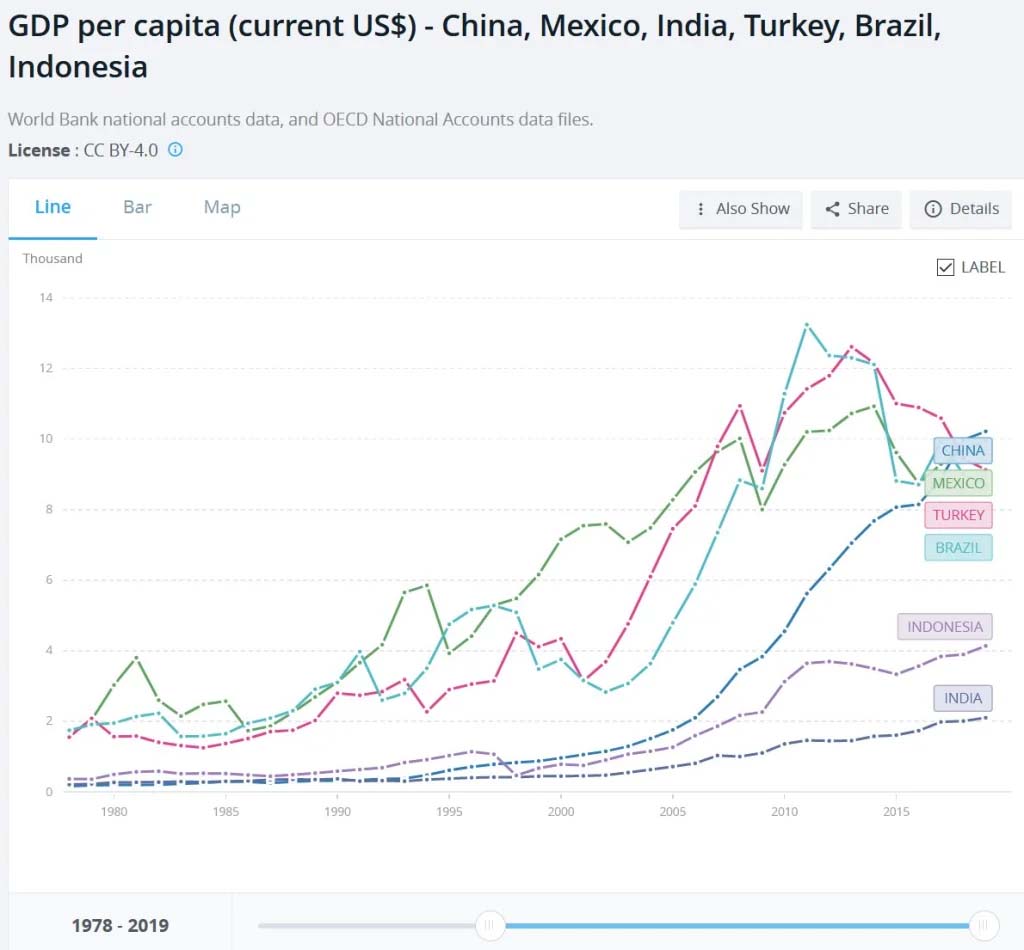

Chinese income not only remains far below that of the imperialist societies, it also remains on the level of other relatively developed but poor, “Third World” capitalist societies. Figure 1 shows that China’s so called rise – while very real and hugely important – in fact represents the country’s path from being among the poorest Third World societies in 1980, to one member of a group of the richest large Third World countries today. An analysis of China’s growth therefore needs to account both for its remarkable success within the Third World camp and also account the reality that it has been unable to escape its membership of the Third World.

Figure 1: China and other major Third World States

GDP Per Capita, 1978-2019

China is the Most Successful Non-Monopoly Capitalist Country

China has become the most successful (or close to it) among the grouping of capitalist societies of a particular type. These “Third World” countries have a much lower income than the imperialist states. Their underlying socio-economic character in relation to imperialism is most accurately described as non-monopoly capitalism. The rapidity of Chinese growth reflects most essentially the rapidity of its defeat of rival non-monopoly capitalist firms and countries. At the same time, all non-monopoly capital is subordinate to the monopoly capital of the imperialist states. For this reason there is a very definite limit to the possibilities for China’s future success so long as retains is current roles within the global division of labour.

The reason it has not been possible historically, and remains impossible today, for countries to move from the Third World to the First World (without the blessing and assistance of imperialism, as was the case for South Korea and Taiwan) is due to the insurmountable scientific, technical and productive monopolies possessed by the imperialist states – insurmountable, that is, within the framework of capitalist competition for production to supply the capitalist world market.

It’s not by chance that the world’s nations are starkly polarised into two distant camps – rich and poor – with a vast gulf between the two. The underlying social basis for this income polarisation is the polarisation of the world division of labour into monopoly labour processes (the most complex labour) and non-monopoly processes, which are typically simple or standardised production.

Monopoly labour processes require a high degree of specialised technical knowledge, are relatively complex and difficult to achieve and replicate and are often based in scientific research and development, the results of which have not yet become generalised.

Non-monopoly labour processes, by contrast, are those which, due to their standardised or simple character, can be carried out by many capitals in many parts of the world – including the Third World. Standardised labour processes are non-monopoly by definition because they are easily replicated.

Individual capitalist firms and national capitals that rely predominantly on non-monopoly labour processes that are easily replicated, generally secure only meagre profits. This is because it is not often possible to raise prices very much for something that is easy to produce. If a capitalist tries to do so, other capitals producing the same thing but selling it cheaper will encroach on their market. Or other capitals can relatively easily invest in production of the same thing.

This non-monopoly type of production/labour process is what predominantly characterises the capitalist expansion in China over several decades. That is the basic reason China can accurately be described as a non-monopoly capitalist state and society.

The exceptional speed of China’s capitalist expansion has had profound impacts on the shape of world trade and investment. However, as non-monopoly capitalist growth, it is qualitatively different from and technically (and therefore socially) subordinate to the monopoly development which is simultaneously occurring in the imperialist countries.

All capital – including non-monopoly capital – must try to compete to improve its market position but can do so only according to its own strengths. This includes competition among monopoly capitals, competition among non-monopoly capitals and competition between monopoly and non-monopoly capitals. The latter is the most relevant for understanding the exploitation of the poor countries (including China) by imperialism.

The essence of competition between monopoly and non-monopoly capital in the productive sphere takes the following form:

Imperialist monopoly capital develops new ways to raise labour productivity through introducing new technology that, as Marx put it, involves “constantly revolutionising the instruments of production” (i.e. radically changes how production is carried out by the introduction of a new technique). The new technique either saves labour time or creates a new advanced product. Either outcome will increase profits because a new product (that is not easy to replicate) can be sold at a high price, while a new technique that saves labour in the production of an existing product will allow the innovating capital reduce its production costs well below the market price. If the new technique is not easy to replicate, then the mark-up can be sustained. These two ways to increase profits – not improving human society or the environment – represent the real essence of the “research and development” push that pre-occupies every imperialist country today.

Against this, Chinese and other non-monopoly capitals attempt to master or simplify existing production techniques. That is, they attempt to take existing monopoly processes (hitherto not easily replicated) and replicate them using their own labour, technicians etc. When successful, this transforms a given process into a non-monopoly process and allows Chinese or other Third World capital to begin to take over that technique. At that point, monopoly capital (if it is unable to counter-attack with a new product or technique) will divest from producing the affected product, abandoning it to the sphere of non-monopoly (typically Third World) production.

Either method of competition can be successful, to some extent, at redistributing some of the surplus value (profits) created by world labour in favour of either the triumphant monopoly or triumphant non-monopoly capital involved. However, they are different processes with correspondingly different possible outcomes.

Successful imperialist development of new technological monopolies can result in sustained above-average profits because new technology is relatively difficult to duplicate. Further, the imperialist economies are characterised by continuous development of new technology so that their above-average profits are more or less permanent. That is why the same group of nations as 100 years ago remains rich today.

On the other hand, when non-monopolies, successfully simplify a previously complex production process, this can bring only a temporary advantage. As soon as a process has been simplified, it can be widely and rapidly replicated by virtue of now being simple or more widely understood. Hence the price capitalists can get for selling products made in this way tends to fall towards production costs far more rapidly. The falling price of non-monopoly products is further accelerated because the increased competition comes from other non-monopoly producers which, by virtue of their perilous and often desperate market position, are more willing to invest in production spheres that are only marginally profitable. The “race to the bottom” applies only to capitals without some kind of monopoly.

The subordinate position of non-monopoly labour processes, their polar opposite technical and social character to monopoly labour processes and the ongoing powerful tendency towards this high-tech/low-tech specialisation in the world economy means that non-monopoly capital represents no fundamental threat to the continuing domination by imperialist monopoly capital. This is why world income is polarised and will remain so.

Monopoly In China

There certain kinds of capitalist monopolies in China, as there are today in all modern capitalist economies, strong or weak. However, some key features distinguish these from the global monopolies characteristic of the rich, imperialist countries and their corporations.

One type of monopoly is principally domestic – such as Alibaba and the large Chinese banks. The large size, large number of customers and large aggregate profit of these corporations reflect their domination over lesser domestic competitors. The largest Chinese banks, for example, have the largest balance sheets of any banks in the world. Yet China does not possess a single multinational bank that competes with the likes of Santander (Spain), BNP Paribas (France) or the numerous US, British and other imperialist banks. This means that no matter their size in China, these domestic banks are subordinate on the world market to imperialist banks. The same is true for Alibaba versus Amazon, Baidu versus Google and so on.

A second form of “monopoly” that certain Chinese capitals possess is global. These companies have a monopoly over certain simple or standard labour processes or the products of these. Where the production of a given commodity (e.g. a standard domestic washing machine) mostly requires simple labour processes, and this labour cannot be easily mechanised, it can be difficult for capital based in the rich countries – which must pay more “expensive” wages – to compete (unless they move their operations overseas). This type of standardised production has increasingly moved to Third World counties as part of the polarisation of the labour division. There, Third World capitalist producers can and do compete against one another for control. Sometimes such processes are taken over by Third World capital which is able to defeat marginal and declining rich country based capitalist firms that are unable to upgrade or are abandoned.

The winners in this competition – a good many of them in China – can and do form monopolies of a sort: monopoly over low-tech and standardised labour processes. This is a monopoly of labour processes that are essentially cast aside from the imperialist countries, or at least from imperialism’s strongest capitalist groups. This type of Chinese monopoly is global, but only in relation to other Third World (non-monopoly) producers because these labour processes are subordinate within the overall division of labour.

The monopoly capitals of the rich countries meanwhile increasingly invest in the domination of high-tech production and research and development of new products, thus moving higher up the “value chain”. It is this dynamic of continuous rich country ascent further up the technology/labour productivity ladder that explains why China has been able to rise but never catch up. Every time Chinese capital masters a new process and moves another step up the technology ladder, by the time China gets there the ladder itself has already begun to be lowered so that the previously high steps are already dropping down into the swamp of low profitability.

Anyone who doubts China’s technological subordination to imperialism only has to look at the evidence from the so called US-China “trade war” – which is really an act of aggression by U.S. imperialism against China.

Technological subordination is the case even for the most successful Chinese company (and possibly China’s only important true multinational corporation) – Huawei – which relies on US, British and other imperialist technology for both its 5G network equipment business and its phones. Huawei’s technical dependence is the reason the United States sanctions against it, if left in place, will ultimately be effective in crushing the company as a high-end producer. Huawei should, however, be able to continue producing second-rate telecommunications systems and phones.

Most tellingly, for the duration of the current US-China trade war, China has not been able to impose a single sanction aimed at blocking the use of a Chinese technology. This is because it has no technological monopolies on the world market. Such is the position that Chinese capital has achieved through four decades of growing its capitalist commodity production.

The “monopoly” that China has to some extent secured for itself is, in other words, a monopoly only over other non-monopoly capital; a monopoly of the non-monopolies and hence an inherently weak and unstable position. It has become one among the strongest Third World Societies – together with Brazil and Mexico – rising in economic strength above other Third World societies like Indonesia and India. But it still remains technically and scientifically, hence socially and economically, encircled, constrained and exploited by the rich, imperialist societies.

The first article of this series outlined the Marxist definition of imperialism as based in the exploitation (appropriation of value) created by workers in one country by the capitalist class of another. The second article showed that China suffers from loss of value that its workers create, not the other way round, and hence must be understood as an exploited, not imperialist society.

This third article has outlined the reason why Chinese capital is forced to sufferer that loss – that it occupies a subordinate position within the world division of labour and resulting from this a non-monopolistic position on the world market. This loss of value due to scientific and technological subordination cannot be overcome within the framework of production for the capitalist market. It is the essential reason why China and all of the poor, “Third World” capitalist societies can be most accurately characterised as non-monopoly capitalist countries.