I was born in 1951. I was in my early teens when the American war in Vietnam started to become news. I just missed out on being old enough or exposed directly enough to be fully caught up in the 60s radicalisation, but it was the 60s all the same that framed the picture of the world that I gazed upon and eventually engaged with. The 60s was a period of multiple, myriad, kaleidoscopic, even hallucinogenic angles of gaze and questioning. Engagement with social and political realities exploded with militant protest movements, subversive culture and the sharing of songs hitherto without voices. The three big movements were probably the women’s liberation movement, the civil rights movement (especially in the United States) and the movement protesting against the Vietnam War. There were many offensives against the status quo during that decade or so.

The atmosphere in the 60s was not only created by these offensives against the status quo in the rich, western countries. After World War Two, there was also a wave of liberation throughout Asia and Africa. World news coverage was populated with names like Mao Tse Tung and Chou En Lai, Ho Chi Minh, Sukarno, Sihanahouk, Nehru, Nasser, Nkrumah, Lumumba, Fidel Castro and Che Guevera. Liberation from colonialism and social revolutions of one degree or another were a fundamental feature of the period. All these leaders, with different gradations, were on the left of politics, even if simply by virtue of the fact that they stood against colonialism, neo-colonialism and imperialism – all of which were the forms that capitalism presented itself most directly in what became known as the Third World. Some, such as Ho Chi Minh, Mao Tse Tung and Castro stood very clearly also for the perspective of social revolution.

Socialist Struggles

As the American war against Vietnam escalated and everybody witnessed on television this war against a Third World people by an alliance of countries from the imperialist West, the contradiction between imperialism and the Third World manifested itself on the streets of U.S.A, Australia and elsewhere. In Latin and South America, the example of Cuba also accelerated the growth of progressive movements around that continent as Chile moved towards electing a socialist government, then doing so in 1970. The Third World was very present in many people’s consciousness. For a significant minority of youth, the Third World presented as a progressive force.

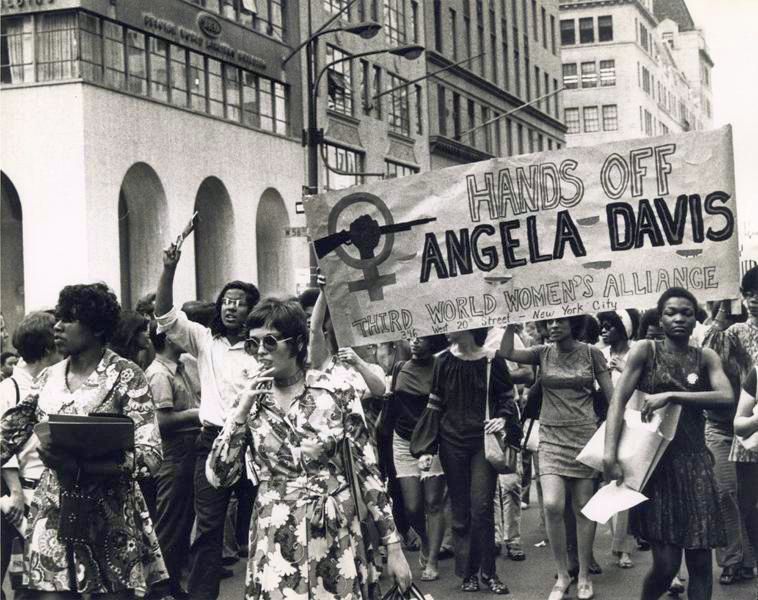

Third World Women’s Alliance marching in the inaugural Women’s Strike for Equality march, New York 1970.

Of course, there was a massive status quo counter-offensive. The dominoes were about to fall in Southeast Asia went the propaganda and it rang true because it was true. China had its revolution. Vietnam’s revolution had well and truly started. The Indonesian left parties were becoming huge. There were communist guerrillas in Malaysia and Thailand. China still talked of U.S. imperialism as a paper tiger. Anti-communist, and also racist “yellow peril” ‘Asian hordes” propaganda focussed on all these as threats. America and Australia sharply divided within itself. But there was still a big minority of youth (even a majority?) for whom the Third World loomed large and its struggles attracted solidarity. The most visible manifestation was the movement against the war in Vietnam. Figures like Fidel Castro and Che Guevera also became icons. The Mao cap was not uncommon at demonstrations.

The Question of Development

There was also another perhaps less revolutionary but still fundamentally subversive worldwide discussion taking place. After WW2, as colonies won their independence, their governments and peoples were suddenly faced with a terrible reality. In the midst of an already rich world, they had been left by colonialism with a legacy of severe under-development. While the scientific and then the industrial revolutions had evolved into 20th century advanced versions, modernising production in all the rich countries, almost none of the progress in production, nor its social and educational foundations, had been developed in the colonies. Capitalist relations of production – the spread of wage labour – now dominated (though by no means saturated) the former colonies, but capitalist industrial production had never been prioritised. Industry was the preserve of the imperial home countries. Universal education was non-existent in the poor countries at a time when, in the imperialist countries, all boys and girls were going to school – and the schools had libraries!

The colonies had been run as dictatorships where even the experience of bourgeois political citizenship was absent. In a country like China, too big ever to be directly colonised, gun boat diplomacy, unfair treaties and every kind of corruption and imperial manipulation kept the country in a state of perpetual chaos and degradation, probably most symbolically represented by one of Britain’s chief exports to China: opium.

The newly independent countries had been plundered and left socio-economically backward: they were “under-developed”. How the under-developed world could become developed was a major discussion – a huge discussion. This was the case in the United Nations where the newly independent countries numerically dominated, though without China being there. In universities, in development agencies, in newspapers, “development” and “under-development” became unavoidable words in any discussion of the world situation. Within the Third World, struggles emerged between those who argued that some kind of socialist planned economy was the path to development and those who argued for Western “assisted” capitalist ‘modernisation’. Out of Latin America, and the study of Latin America, came Dependency Theory and the calls for struggles of national liberation.

For the majority of youth radicalised during the 60s and 70s, solidarity with the struggles of Third World peoples’ for national liberation and for a transition to socialism and against imperialism was pervasive. There were small exceptions among ultra-left groups trapped in sectarian dogmas that distanced themselves from these movements while documenting their imperfections. But solidarity with the actual existing movements for national liberation and socialism in the Third World framed the majority outlook. In the 1980s this was boosted with the emergence of the Nicaraguan revolution which attracted significant active solidarity, along with its Cuban ally, even as the broader wave of youth radicalisation waned and as the right wing picked up momentum, sensing the collapse that was to come in the USSR.

Solidarity with the Third World Today

If you have grown up in the 90s or this century, you have experienced a very different world. Apart from the marvellous example of Cuba, there are no more names such as Mao Tse Tung and Chou En Lai, Ho Chi Minh, Sukarno, Sihanahouk, Nehru, Nasser, Nkrumah, Lumumba, Fidel Castro and Che Guevera – leaders of mass struggles against colonialism or governments that defied imperialism. It is only in the very last period that we have had Chavez. Mostly, the Third World names that have echoed have been Suharto, Widodo, Modi, Mahatir, Mubarak, Erdogan and the like.

During the most recent period it has been the names of leaders of conservative states or countries appearing to transition away from socialism, even in China, that dominate. Equally starkly, the discussion of development and under-development has disappeared. Now, reference to under-developed countries has been transformed to talk of emerging economies or even “emerging markets”. Countries that used to stand as a challenge to imperialism have now been embraced into the G-20, despite the fact that the prosperity and production power gap between the top 6 countries and the rest makes the embrace just another part of the stranglehold of the rich nations over the poor.

The objective world economic conditions retain basically the same features as three decades ago – indeed a hundred years ago. The world is polarised between rich and poor nations: with the rich also dominant militarily and politically, as well as economically. With the exceptions of Bolivia, Cuba, Vietnam and Venezuela, most of the poor nations now have governments who have set out on a path of capitalist economic growth as the path to “catch up” with the advanced countries. In most cases, this has meant an end to appeals to collective struggle and idealism, let alone to socialism. The extent to which there are appeals to idealism, they are around the question of sovereignty and the right to struggle to catch-up using capitalist methods, without having to face aggressive containment from imperialist countries.

This cannot so easily inspire the same kind of radicalisation and solidarity among young people as was the case in the 60s and 70s. Neither the leaders nor the governments of many of these countries are inspiring as democratic and socialist examples nor are they aiming at optimal participation of their people in either political decision making or in enjoying an egalitarian distribution of wealth. In many cases, they are top-down instructional regimes, sometimes autocratic, suppressing their people when they rebel against maldistribution of wealth or denial of political rights. This anti-popular character alienates them from the whole idea of democratic popular participation and makes it inevitable that when they need to defend themselves from imperialist aggression and containment, they must resort to diplomatic, military and commercial manoeuvre against imperialist governments rather than try to appeal with argument to the publics of the imperialist countries. If you can’t appeal to democratic participation and struggle of your own people, you won’t be trying it elsewhere.

It is also the case that the capitalist path to growth does not allow for “catch-up” by the poor nations with the rich. The massive polarisation and rich-poor gap is a permanent feature of this highest (last) stage of capitalism. The rich countries, with their imperialist states and ruling classes, permanently monopolise the ability to accelerate the development and revolutionising of the means of production – that is, of the ability to increase generalised labour productivity through technological advance. The rest of the world is excluded from this monopoly: the globe is divided into monopoly and non-monopoly capitalist states – with only a handful of states fighting the prolonged, gruelling transition to socialism.

Defending the Chinese nation’s right to be free of aggressive imperialist containment of its development is the correct thing to do. Imperialist containment is keeping China poor. At the same time, defence of China’s national rights means supporting China’s attempt to progress through a capitalist path, which is bound to fail, and which also reproduces great internal inequalities. This presents a challenge for international solidarity and building an anti-imperialist left that is more complicated than when China appeared to be on a socialist path and to have high levels of mass participation in its politics – which was how China was seen by most of the international Left until the early 1970s. There is no Maoist cap that can symbolise the situation for China today. The politics of explaining it now presents a complicated challenge. But the complexity cannot distract us from the necessity of defending the Chinese nation’s sovereign right to pursue development free of constant aggressive containment from U.S. imperialism and its allies. The social progress of 1,400,000,000 people is at stake.

I used the word “development” in the previous paragraph as a better word than “growth”. The polemics of earlier decades about development and under-development created concepts, even in ruling class institutions such as the United Nations, of things such as the Human Development Index, which starts to define progress in a more sophisticated way that a simple measure of the dollar value of goods and services sold in the world’s markets. However, any and all forms of development being pursued through a conscious capitalist strategy in the end means that ‘progress’ will be measured in the dollar growth of goods sold on the market. Various effects of this can be ameliorated through government policies that insist that non-dollar growth targets also be prioritised. This has occurred in various countries, rich and poor, at different times and for different periods of time. The laws of capitalist economics, however, always press things back the other way, inevitably and without rest.

Cuba

Cuba is the example of a country able to institutionalise, to embed, the amelioration of the impacts of the capitalist framework to the best effect and for the longest period. It has done this by largely abolishing the domestic market in most economic spheres, and completely abolishing it in sectors such as health, education, housing, and culture that greatly influence quality of life. It has also instituted a state monopoly on foreign trade and very high degrees of regulation and taxation of the economic sectors the state does not have the resources to operate directly.

Still, while operating within an international capitalist framework, it is also the object of very aggressive containment by U.S. imperialism, manifested in extreme economic sanctions and ongoing blockade. This is the basic reason Cuba is unable to rapidly and explosively develop its productive forces. Its outstanding achievement is its very high levels of amelioration of the effects on Third World countries of the imperialist economic system. Cuba has been able to sustain this even since the collapse of the Soviet Union – previously its main trading partner – which caused an 80 percent decline in export earnings and forced the state to retreat in certain areas. The retreat has meant permitting a larger space for the operation of a market for some goods and services in certain areas – such as allowing small private restaurants and cafes as well as joint ventures between the state and foreign capital in the tourism sector.

Cuba also points to how an ideal of socialist development can be understood. Security of well-being (health, food and housing) is the base commitment, after that comes culture, including the culture of solidarity with other human beings in their struggles against oppression and for progress. This orientation, which includes striving for the maximum popular participation in political life that objective conditions allow, also means that Cuba has confidence in being able to use political methods in defending itself from the U.S. imperialism. It can not only criticise the deprivations of the U.S. government, but also feels comfortable and confident in presenting its society to the American people, and other peoples of the world. The Chinese government is not in a position to do the same thing. Its governance is top-down, issuing instructions from above downwards. The government collaborates with US corporations to supply Chinese workers to be super-exploited and also produces its own billionaires and other forms of over-conspicuous consumption. While there has been huge improvement in the lives of the Chinese people since the revolution, which continues on many fronts today, the system operates with many more unattractive and debilitating contradictions than Cuba. Of course, a government responsible for the progress of the fate of a formerly impoverished (and still poor) and oppressed country of over a billion people, with different linguistic, ethnic and cultural components, has a very problematic task.

Cuba was able to consolidate its system to its current level during a period where it received material support and military security from the Soviet Union. This important advantage has not been available to Venezuela, nor will it be available to any other Third World revolutionary government in the foreseeable future. The Venezuelan revolution has not developed into a revolutionary war that would smash the Venezuelan capitalist class. That class was politically defeated after the failure of its counter-revolutionary coup in 2002 – which split the armed forces – and the bosses’ lock-out of the oil industry 2002-3. These events allowed the revolutionary forces led by Chavez to gain decisive control of the army and the most important economic sector – oil. Since losing control of the army – the highest and most decisive element of the broader state apparatus – the Venezuelan capitalist class no longer possessed the state power to enforce its dictatorship and hence lost political power. However, while it has been politically defeated it has not been smashed as a social class. It still owns and controls important parts of the economy, including the corporate media, which the Venezuelan working class has not yet conquered.

Venezuela

The Venezuelan revolution is the first socialist revolution that has not escalated to a revolutionary war, as happened in Russia, China, Vietnam, and Cuba. The revolutionary state cannot risk creating a situation that would allow a U.S. military intervention. U.S. imperialism itself is hesitant to escalate to full-scale war against the revolutionary masses, fearing it might spark a continent wide surge in anti-imperialism. U.S. imperialism will not do so unless it thinks it is absolutely necessary, but it will do so if necessary. This leaves Venezuela in a position of being subject to escalating economic sanctions and aggressive harassment, as in Cuba, but without the assistance of a Soviet Union before it has ever had the chance to consolidate a new system. It has faced the aggression of U.S. imperialism in a unipolar world since the beginning of its process. This situation means that the Venezuelan revolution, which is now two decades old, has been fought under very unfavourable economic and material conditions and under the shadow of military intervention. Such difficulties, especially when faced by a country with an ‘under-developed’ economic and social structure, inevitably make it prone to all manner of negative distortions and problems.

Anti-imperialism mural in Caracas, Venezuela.

While presenting a less immediately inspiring picture than Cuba, especially with both bourgeois and some left media seizing on every distortion and difficulty to prove it has failed, solidarity with the Venezuelan people, their government and their revolution must also remain a high priority for socialists.

Complexity of anti-imperialism today

China and Venezuela are just two examples – quite different in their specifics – of the more complicated political explanations needed about the necessity for solidarity with these two peoples. But these explanations must be part of any anti-imperialist socialist’s political education work. Underpinning this approach is the understanding that there is a global imperialist structure where a handful of countries, with incredibly rich and powerful capitalist classes and states, still dominate the world economy and are able to keep Third World countries poor, including a country like China. Defending these countries, including countries with objectionable states and economic systems, from the aggressive containment by the dominant imperialist powers is absolutely a necessary duty for socialists.

To the extent any state, including a Third World state, is the state of a national capitalist class, it will pursue its own interests first, which may sometimes, but not always, be at the expense of other Third World capitalist classes or countries. The states and classes of the stronger – or less weak – country may bully or otherwise manoeuvre against others – which is a negative and destructive action. This phenomenon, when it does occur, must be distinguished from imperialism itself, which is a form of capitalism – its highest stage. Imperialism is a system of global dominance of a handful of oppressor nations and their states over the rest of the word, not the individual cases of opportunistic manoeuvre of one stronger country against another.

It is also possible for economic relations between non-imperialist capitalist countries to have a combination of positive and negative consequences for one or both countries involved. Economic co-operation among Third World (non-monopoly capitalist) countries, even when designed to strengthen their position vis-à-vis imperialist countries, still must work in accordance with capitalist economics. The extent to which such deals are mutually beneficial is likely to be unequal.

The political work of socialists must always include ongoing explanation (propaganda) of the nature of imperialism (as the highest form of capitalism), of the system where a handful of oppressor nations – the same few countries over the last 120 years – oppress and exploit the rest. None of the Third World countries, including the largest of them such as China, have gained entry or are likely to gain entry into the imperialist club. This is how capitalism, since the beginning of the 20th century, works. To fight to end capitalism, you must understand it. To not understand imperialism in this way is to not understand capitalism. To systematically mis-educate people aspiring to end capitalism on this question is destructive to this struggle. The mis-education can take the form of presenting analysis that denies the imperialist reality, of arguing or implying, for example, that Third World countries can escape the rich-poor polarisation even under world capitalism.

It usually will also take the form of offering political responses to and explanations of actual political developments that benefit imperialist power. Tensions between a growing non-monopoly capitalist country such as China and an imperialist country such as the United States caused by U.S. imperialism’s aggressive containment of China’s development is falsely depicted as an inter-imperialist struggle where the Left should remain neutral. Distortions and contradictions in Venezuela’s revolution stemming from its inability to smash the capitalist class, while that class has protection from the United States in a unipolar world, result in criticism of the Venezuelan leadership being prioritised far ahead of supporting it against imperialism, even some times to the extent of abstaining totally on the latter. The very ideal of improving a Third World people’s material and cultural welfare such as has occurred in Cuba (and also to an extent in Vietnam) is inhumanly negated as being meaningless because various Lefts’ fantastical schemas of how to rule have not been followed. All of these political lines’ bankruptcy is ultimately destructive of building a strong socialist struggle.

Anti-imperialist politics as a domestic political question

In all countries of the world, presenting a clear explanation (propaganda) of how the current, highest stage of capitalism is imperialism, and of how that works, is a central task for socialists. It will be impossible to defeat capitalism if you don’t know how it works. Joining, helping to strengthen and – where possible and necessary – leading struggles to defeat imperialist aggression in whatever form it takes and giving solidarity with those who are fighting its aggression, even when we differ with or oppose other features of those under attack, is always a key duty. Explanations of how imperialism works will never be effective, even simply as explanations, if socialists also do not seriously, within their resources at any particular time, also act on their understanding.

The significance of a framework as described above has an additional crucially important dimension beyond being an obvious central task and fundamental duty for Marxist socialists. In any country that is a member of the small imperialist club, such as Australia, fighting imperialism means, of course, fighting our own ruling class whose economic fortunes require them to both protect their privileges in the international imperialist structure and convince the Australian people (i.e. the working class) that it is necessary and legitimate to protect imperialist privilege.

Since WW2, Australian governments have allied themselves with the primary imperialist power in wars and military interventions in Korea, Malaysia, Vietnam, and Cambodia; and later against Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria. It also supported the NATO operation against Libya. The Australian government has supported the propaganda against Cuba and Venezuela. It established a long supportive relationship with the reactionary Suharto military dictatorship in Indonesia, supported and covered up the war crimes of the genocidal Rajapaksa regime in Sri Lanka among other examples. Although awkwardly juggling profit concerns, it has aligned itself with U.S. imperialism’s aggressive containment policy towards China.

All of these policies target Third World countries. To justify these aggressions, there must be a constant flow of propaganda and much of this relies on racism and xenophobia. Back in the 1950s it was the ‘red peril of the yellow hordes’ and the posters showing dominoes falling over, starting in China. There has been a long line of variants used. We were told by the Howard Government in 2001 that Third World parents would throw their babies overboard into the ocean in order to gain entry to Australia. They only pretended to be refugees. After 9/11, Islamaphobia became popular among the ruling class ideologues. Now it is that China wickedly wants to control the South China Sea but the huge U.S. fleets in the Pacific and patrolling the seas off China since WW2 are benign. The list is endless.

The effort to indoctrinate Australians with racist and xenophobic ideas has never stopped and can never stop under imperialism. War or other aggression against a Third World country can be necessary at any moment – in fact Australian forces are still deployed in Afghanistan and parts of the Middle East. Australia still votes in support of Israeli aggression against Palestine and Palestinians.

It is very necessary for the the Australian capitalist class that working people both see the Third World, the peoples of the oppressed nations, as not just “failed nations” but as “failed peoples”. This both helps justify imperialist interventions against them but also strengthens feelings of the rightness of the very significant relative privilege that the majority of the Australian population enjoy in terms of quality of life compared with the peoples of the Third World. Ordinary human beings – that is people not integrated into any national elite – do not spontaneously feel justified in having a life style many times better than others, including people in other countries. That this privileged situation can be felt as right and justified requires the constant inculcation of a racist outlook, of racist entitlement.

Apart from the outright racist and xenophobic agitations historically associated with Australian imperialism, the “yellow hordes”, “red peril”, falling dominoes propaganda and more recently Islamaphobic, anti-refugee and now anti-China agitation, there has been an additional longer-term undermining of sentiments of solidarity with peoples of the Third World. This has been more subtle and devious, but no less destructive of solidarity. The whole idea of there being developed and under-developed countries has vanished. Even the very moderate liberal idea that under-developed countries needed support (genuine support) to develop has vanished from the main stage of political debate. In Australia, almost in direct proportion to the strengthening of racist and xenophobic propaganda and policies, commitment to overseas aid programmes has greatly diminished. Where expenditure has been maintained, it is even further transformed into so-called “soft power” measures vis-à-vis what used to be called under-developed countries.

The elevation of some under-developed countries to be considered as among the “emerging markets” and the inclusion of some of these into the G20 has helped this process. These countries while having grown their middle classes with spending money, still have miserably low per capita incomes and all score low on any kind of human development or social progress index. The claim that they are now “emerging” is used to spread the idea that they no longer need any transfer of wealth from the rich countries. Sometimes, as is the case now with China, they are even depicted as not just an emerging market but as an emerging threat, implying a threat to the quality of life of all in the rich countries. To the extent that they experience any backward slide after having started to emerge, it is said that this is because of the mistakes of their incompetent or uncooperative leaders. In any case, we hear “why give them aid? Their economies are almost as big as ours.” Figures about “sizes” of economies usually ignore miserably low levels of per capita income, per capita accumulated wealth, and per capita infrastructure development. This whole collapse of the development versus under-development discussion subtly but devastatingly reinforces under the surface feelings of the rightness of the higher quality of (material) life in the imperialist countries, amongst all classes.

The ruling ideas of any society are the ideas of the ruling class – the ideas the ruling class wants to dominate. It has massive resources to help with this. The imperialist complex of ideas connecting race, foreignness and privilege here in Australia have additional roots which historically precede the 20th century rise of the imperialist world. Australia is a country born of invasion and occupation. British forces and people occupied Australia and declared it an empty continent free of human beings. The indigenous inhabitants, who were dark skinned, were basically declared non-human. The intellectual and moral supremacy of white skinned people became official ideology, and deeply embedded into colonial pre-Australian and then Australian popular culture and official policies, include much genocidal activity. This was later further reinforced as prejudice based activities arose against Chinese migrants and also Pacific cane plantation workers – some of who were enslaved. Racism has long been a feature of Australian political and cultural life and has been relatively easily built upon in the imperialist period.

These racist and xenophobic attitudes work not only to strengthen the feelings of rightness of Australia’s developmental privilege and of the legitimacy of acting to defend “Australian interests” anywhere in the (Third) World but also work to divide the working class within Australia, while at the same time fusing many segments of the working class with the ruling class in its imperialist ideas of the national interest. These attitudes also separate many Australian workers, of whatever ethnic background, from Australia’s First Nations, without doubt the section of the population that has suffered the most sustained and intensive and deadly oppression and persecution, to this day.

Explaining the irrationality of racism (morals and intelligence are not to be found in skin pigment) and the immense suffering it has caused and fighting its current manifestations within Australia against First Nations people is a necessary task and duty in its own right. The same applies to racial discrimination against other ethnicities or in the form of Islamophobia.

At the same time, we must understand that it will be impossible to conduct an effective fight against any kind of racism in an imperialist country if imperialism itself is not fought. Anti-imperialist political work is NOT just a matter of doing what solidarity work we can with this or that overseas struggle. Such solidarity work with foreign struggles is a necessary task, indeed a duty, and can be very important in helping determine the positive outcome of a struggle, as was the case with the Vietnam War and perhaps also East Timor. However, it is also absolutely necessary work in weakening the ideological hold of any national ruling capitalist class over its working class, including defeating racist and xenophobic ideas at home. All socialist organisations need to have this work among their top priority tasks. Left organisations which deny the existence of the global imperialist structure and refuse to defend those under attack from imperialism, are doing damage. Even the most sincere, worthy and militant campaigns against domestic racism and xenophobia will make only little progress if they are not part of a strategy that also explains the system of oppressor and oppressed nations as the contemporary form of global capitalism and calls for a fight against it. This necessarily involves concretely international solidarity work in defence of those exploited and poor countries, or movements within countries, resisting imperialist aggression of whatever form. Where those resisting such aggression, oppression and containment are themselves capitalist or autocratic states, their limitations and contradictions will need to be explained, but defeating imperialist aggression must remain the priority.

Active solidarity with Third World struggles is a significant part of any antidote to racism as it will mean an increasing understanding of the situation of Third World peoples, making clear that their sufferings and the limitations to their development are not the consequences of being failed peoples but primarily flow from being imprisoned by an imperialist structure and damaged by imperialist aggression. It will also reveal that even when their own regimes are part of the problem for their development, the character of the regime flows from its comprador status or distortions that grow under the pressure of aggression and containment. But more than that, understanding the seriousness and richness of these peoples’ struggles can inspire others about the levels of courage, humanity and imagination which human beings in struggle can rise to. When young people, or anybody, in the imperialist countries have been inspired by the Chinese, Vietnamese, Cuban, Venezuela peoples’ struggles for socialism, or the Filipino, Indonesian and East Timorese struggles against oppression, it is a powerful antidote to racism.

It may be the case that in the long run, or even in the medium term, successful struggles for national liberation or for socialist governments in Third World countries find it hard to survive or sustain themselves free of destructive distortions. They are not only constrained by the difficulties of building ‘socialism in one country’ in an imperialist world, but are challenged to do this from a low base of economic development and where all the most advanced means of production are monopolised by the imperialist countries.

In this period of unipolar imperialism, in which the role of the United States as the pre-eminent aggressive force, the growth of anti-imperialist political thinking and activity inside the United States becomes more important. Prior to the collapse of the USSR, national liberation and socialist movements in the Third World had protection from two major sources: the USSR and from the solidarity of anti-imperialist solidarity groups and movements wherever they were strong. Today, with the USSR gone, alliances between socialist governments and various governments of non-monopoly capitalists states in self-defence against imperial aggression will be important. One example is the economic and political cooperation by Venezuela with Iran and also China. But as these governments are all under imperialist attack of one kind or another, and suffer from their own weaknesses, such alliances and cooperation can’t replace the protection offered by the USSR when it was a super-power.

In this situation, anti-imperialist campaigns and movements must play a bigger role. One critical aspect of this that needs greater attention here is the need for active solidarity by socialists in Australia with anti-imperialist campaigns and any anti-imperialist Left groups inside the United States. The U.S. is the largest source of direct imperialist intervention and aggression even when this global policing role also serves the interests of smaller imperialist powers like Australia. The indispensable imperialist role of the U.S. state and armed forces also increases the importance of anti-imperialist social movements within the United States.

Anti-imperialist solidarity campaigns in Australia may need to encompass campaigns in support of progressive anti-imperialist activity in the U.S., especially when it comes under attack from the U.S. state. It would have been excellent, for example, if there had been the will and capacity to carry out actions in solidarity with those defending the Venezuelan Embassy in Washington from occupation by forces loyal to Juan Guaidó, the hapless and unelected “President” and would-be dictator that Washington was then attempting to install. Collaboration between anti-imperialist socialists in Australia with left groups involved in these activities, such as the Answer Coalition and Code Pink, should already be an area of activity.

Eventually, but sooner rather than later, revolutions are necessary in the imperialist countries themselves. Yet, so far, since the end of the Second World War – i.e. for seven decades – the revolutions that have occurred have almost exclusively been located in the Third World. Given the continuing imperialist oppression, exploitation and the growing rich-poor country divide, there will no doubt be more in the future. It will be a crime of strategic immorality to underestimate the blow of any Third World struggle’s victory inflicts on imperialism. It would be equally wrong to underestimate the contribution to the political radicalisation of peoples, especially youth, in the imperialist countries of such struggles, and their victories. Relating to, understanding and supporting the actual mass struggles against the imperialist system, as they actually occur, is an indispensable step in our own working class being prepared for its own assault on imperialism’s heartland.